"I Learned From the Last Generation of Manhattan Project Veterans”: Patrick McClure's Journey From Los Alamos National Laboratory To SpaceNukes COO And The Revolutionary Project Kilopower That Changed Everything

Patrick McClure, SpaceNukes COO, shares his journey from Los Alamos to revolutionizing space nuclear power with Project Kilopower. Mentored by Manhattan Project veterans, he broke decades of stagnation with an innovative reactor demonstration that reignited America's space nuclear program.

In the shadow of Los Alamos National Laboratory, Patrick McClure challenged decades of space nuclear power stagnation. After watching his mentors—aging Manhattan Project veterans—retire without seeing their visions realized, this petroleum engineer turned nuclear specialist made a fateful decision. Rather than continue the cycle of perpetual research without deployment that had plagued space nuclear development for nearly half a century, McClure and a small team of scientists would break the pattern.

Their weapon of choice was a reactor mockingly named after Homer Simpson's favorite beer—"Duff"—cobbled together for less than a million dollars. This modest demonstration, lighting little more than an LED display, reignited America's dormant space nuclear program. Now, as Chief Operations Officer of SpaceNukes, McClure stands at the helm of a private enterprise poised to accomplish what government agencies alone could not: returning American nuclear reactors to space and potentially transforming humanity's relationship with the final frontier.

You began your career in petroleum engineering before transitioning to nuclear reactor design and eventually space nuclear power. What inspired this journey, and how did you become involved with space applications of nuclear technology?

My exposure to space reactor technology began early in my career. My first substantial engineering position was at Science Applications International Corporation, now known as Leidos, a major defense contractor. This was during the 1980s when President Reagan's Strategic Defense Initiative—colloquially called 'Star Wars'—was creating significant funding opportunities. One component of this initiative was Space Power 100, a program aimed at developing a 100-kilowatt space reactor. For perspective, an average household consumes roughly one kilowatt daily, with peak usage around three kilowatts when running major appliances like air conditioners. So this represented an ambitious attempt to deploy substantial power generation capability in space.

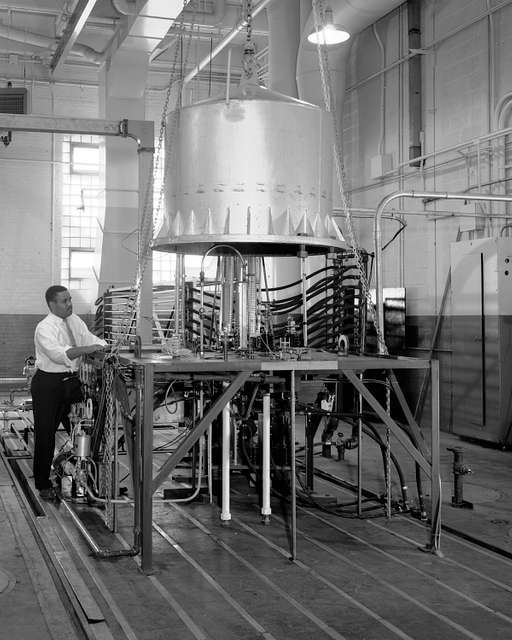

I was involved with these projects before joining Los Alamos, which had been the epicenter of space reactor development since the late 1950s. Under the Atomic Energy Commission, Los Alamos was tasked with developing much of this foundational technology. Their flagship early initiative was Project Rover, focused on creating nuclear thermal rockets—distinct from conventional space reactors in that they channel hydrogen gas through the core, heating it to approximately 3000 Kelvin to generate rocket propulsion.

Project Rover was Los Alamos's primary focus from the late 1950s until its congressional cancellation in the early 1970s, after which the lab continued its space reactor development work at a reduced scale. Although I was peripherally involved, space nuclear technology wasn't my primary focus initially. By the 2000s, my role had evolved to managing teams working on space reactors, and toward the end of that decade, I became directly involved in several projects. It was then that colleagues and I determined to take a different approach to space nuclear development. Despite my long association with the field, it truly became a professional passion only around the late 2000s.

When I joined Los Alamos in 1994, the laboratory was undergoing a significant transformation. Looking back at its history through the 1950s and 1960s, the lab had been predominantly led by Manhattan Project veterans—individuals who, as portrayed in the film "Oppenheimer," had been quite young during the project but had since risen to leadership positions and were directing a wide range of innovative initiatives.

By the 1980s, however, the institutional focus had shifted from innovation toward maintenance and stewardship. This change was particularly pronounced by the late 1980s, when the United States had ceased both the development of new nuclear weapons and nuclear testing activities. The laboratory was adapting to this new reality.

What proved invaluable for early-career professionals like myself arriving at LANL in 1994 was the presence of these pioneers who had spearheaded the original projects. We benefited tremendously from their mentorship, their institutional knowledge, and their enthusiasm for areas of research they believed would eventually return to prominence. Unfortunately, that resurgence didn't materialize as anticipated.

As this generation retired and my contemporaries assumed leadership roles, we observed a concerning pattern: government funding tended to support research projects without clear pathways to deployment, particularly in space. What ultimately ignited my passion for space reactors was the desire to break this cycle—to move beyond perpetual research toward actual deployment in space. Several colleagues and I decided to challenge this status quo directly.

As the Los Alamos National Laboratory lead for the Kilopower project, you overcame significant political and safety barriers. Could you walk us through the novel process you developed to navigate these challenges?

By the late 2000s, we initiated discussions with NASA about constructing and testing an operational space reactor—something that hadn't been accomplished since the late 1960s or early 1970s. While we found interested parties within the agency, convincing key stakeholders would require demonstrable proof of concept.

In 2010, our principal reactor designer, Dave Poston, was appointed to a joint NASA-Department of Energy initiative to evaluate NASA's long-range objectives for the next 10-20 years—what are commonly termed "decadal surveys." This particular effort was led by the distinguished John Casani, whose credentials included directing the Voyager, Galileo, and Cassini missions. His task was to determine the scientific community's priorities for the coming decades.

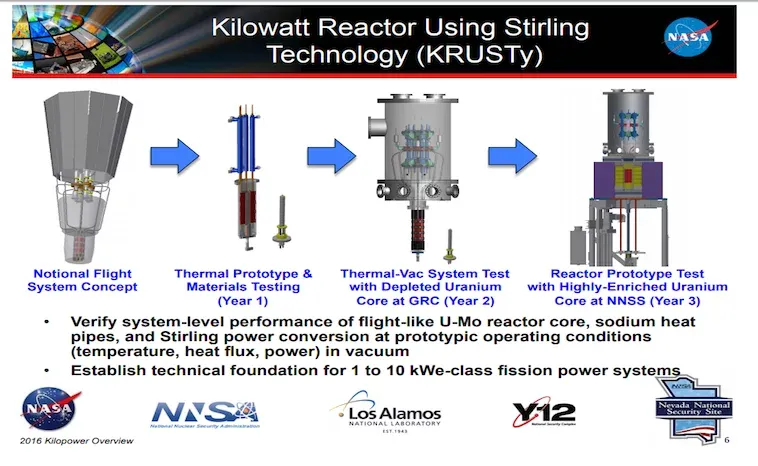

Space reactors invariably appeared on these wish lists, but historically, we'd dismissed such proposals as prohibitively expensive—typically costing billions of dollars. This time, however, the team was encouraged to approach the challenge from a different angle. Dave Poston collaborated with NASA's Lee Mason to conceptualize a lower-power space reactor that would be more economical and feasible with existing technology, minimizing the need for extensive research and development.

As with many NASA reports, this one initially gained little traction. Nevertheless, throughout 2011, we continued advocating for this concept in our conversations with NASA representatives. The persistent obstacle was the Department of Energy's perspective that such a project would require funding levels Congress would be unlikely to approve.

We maintained that our approach could substantially reduce costs, but NASA understandably requested verification of these claims. This prompted us to develop a proof-of-concept project that we called 'Duff.'

The Duff Demonstration

The name 'Duff' reflects Dave Poston's practice of naming his reactor designs and computer codes after characters from 'The Simpsons'—Duff being the fictional beer that Homer Simpson drinks. For this demonstration, we utilized an existing reactor configuration at the Nevada Test Site called 'Flat Top.' This system consisted of a highly enriched uranium core—a sphere of approximately 17 kilograms—surrounded by natural uranium reflectors to redirect neutrons back into the system for criticality.

We fortuitously discovered that this core and reflector assembly featured a half-inch aperture designed for sample testing. This opening allowed us to insert a half-inch heat pipe—essentially a simple metal tube containing, in this low-temperature application, water. At higher temperatures, such systems might employ liquid metals instead. The fundamental principle involves boiling the liquid at one end, allowing it to travel at sonic speeds to the opposite end where it condenses, with a wick structure utilizing capillary action to return the fluid to complete the cycle.

Space Nuclear Power for Mars - David Poston - 23rd Annual International Mars Society Convention

This heat pipe transferred thermal energy from the core to a Stirling engine—a straightforward thermal-mechanical conversion device commercially available even on consumer sites like Amazon. These engines operate by applying heat to one section while cooling another, creating oscillatory piston movement that drives a magnet through a wire coil, effectively functioning as an alternator to generate electricity.

The significance of this Duff project was its remarkably modest budget. We secured limited internal funding from both Los Alamos and NASA, completing the entire experiment for approximately $750,000—an exceptionally economical figure in government research terms. Our objective was simply to demonstrate the complete system chain: fission heat generation powering a Stirling engine to produce electricity—sufficient to illuminate a small LED display.

This seemingly basic demonstration provided NASA management with crucial validation that we could design, construct, and test a reactor within an actual nuclear facility, adhering to all regulatory protocols, without incurring prohibitive costs. This success established the credibility necessary to pursue a more flight-representative prototype.

Securing Funding and Team Assembly

Following this demonstration, we developed a comprehensive proposal involving NASA, Los Alamos, the Y-12 National Security Complex (responsible for fabricating our uranium core), and the Nevada Test Site (our designated testing location). While NASA deliberated on their participation, we explored funding avenues within the Department of Energy.

It's important to understand that the Department of Energy operates through multiple distinct organizational structures. One division oversees commercial nuclear energy, while another—the National Nuclear Security Administration—manages the nuclear weapons program. We successfully made the case to the National Nuclear Security Administration to co-fund this initiative alongside NASA. The funding allocation comprised $12 million from NASA and $6 million from the National Nuclear Security Administration, establishing the financial foundation for what became the Kilopower project.

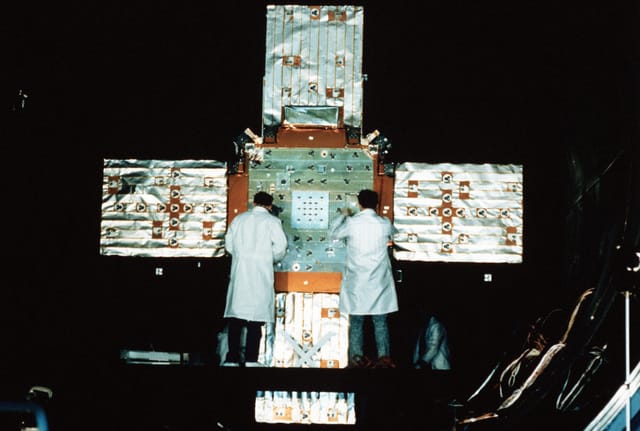

Following Dave Poston's naming convention, the test system was designated KRUSTY (Kilopower Reactor Using Stirling TechnologY). This program represented a significant milestone—our first opportunity to design, construct, and test a space reactor since the late 1960s and early 1970s. This marked a decisive break from decades of conceptual development without physical implementation.

Mission Applications

Lee Mason, who had collaborated on the original 2010 study, had subsequently advanced to a senior position within NASA's Space Technology Mission Directorate. His advocacy for Kilopower centered on its versatility across multiple mission profiles.

One compelling application involved deep space exploration. With a reactor-powered spacecraft, we could operate ion thrusters continuously, fundamentally transforming our approach to distant objects. Rather than the high-velocity flybys exemplified by the New Horizons mission to Pluto, reactor-powered propulsion would enable spacecraft to decelerate and establish orbital trajectories around these distant bodies. Similarly, when approaching smaller celestial objects with minimal gravitational influence, such as Saturn's moon Enceladus, this capability would allow orbital insertion rather than brief encounters, facilitating detailed studies of features like the water plumes that might harbor evidence of extraterrestrial life.

Kilopower: A Gateway to Abundant Power for Exploration

Additionally, we recognized the technology's potential for surface operations on the Moon and Mars. Our most significant endorsement came from the Mars architecture team at Johnson Space Center, whose strategic planning for Martian missions identified Kilopower as a critical enabling technology. This institutional support proved instrumental in generating enthusiasm throughout NASA.

Technical Specifications and Implementation

The Kilopower system was conceptualized with a scalable output range of one to ten kilowatts electric. To minimize nuclear activation of the testing facility, we elected to develop and demonstrate the lower bound of this spectrum—a one-kilowatt reactor prototype.

Our project assembled a multidisciplinary team of specialists: Dave Poston served as our reactor design lead; NASA Glenn contributed Marc Gibson, an accomplished engineer in his forties, as our NASA technical liaison; I managed the Los Alamos component and navigated the regulatory approval process; Chris Robinson's team at Y-12 handled the challenging uranium core fabrication; and we partnered with highly skilled technicians at the Nevada Test Site who would execute the hands-on experimental work.

This collaboration initiated a three-year development program. The first year focused exclusively on electrically heated testing—simulating nuclear heat input to validate the thermal performance of our heat pipes and the operational characteristics of the Stirling engines. Like most engineering endeavors, this phase necessitated several design refinements. The second year concentrated on operational planning—developing detailed procedures for our Nevada deployment, establishing testing protocols, and finalizing system integration methodologies.

Regulatory Innovations

Concurrently, I engaged extensively with the regulatory authorities at the Nevada site—officials from the National Nuclear Security Administration responsible for safety and compliance oversight. My objective was to identify their specific requirements for regulatory approval, addressing a fundamental challenge that continues to impact nuclear innovation in the United States today.

The primary regulatory hurdle we encountered stems from a fundamental paradox: regulators require computational models to be validated against empirical data, yet for novel reactor designs, such validation data doesn't exist until testing occurs. This creates a classic 'chicken-and-egg' dilemma—we needed authorization to conduct tests that would generate the very data ostensibly required for that authorization.

To resolve this conundrum, we proposed an innovative, graduated testing approach. First, we would conduct preliminary measurements at minimal reactor power to limit radioactivity. This would be followed by slightly higher-power tests, collecting data to verify our modeling accuracy. Based on this progressive validation, we would then provide regulators with a sealed prediction of reactor behavior at substantially higher power levels. If our predictions proved accurate within specified tolerances, this would justify regulatory approval for full operational testing. Conversely, significant discrepancies would necessitate recalibration of our models before proceeding.

Dr. David Poston - Small Nuclear Reactors for Mars - 21st Annual Mars Society Convention

Fortune favored our methodology—Dave Poston's predictions proved remarkably accurate. I had established acceptance criteria allowing for temperature variances of ±10%, but our actual results deviated by merely one degree from predictions. This exceptional precision convinced our regulatory partners at the Nevada site of our analytical capabilities, validating our experimental approach and clearing the path for full nuclear testing under our pre-approved experimental protocol.

Successful Testing

We commenced the final phase of testing in October 2017. The comprehensive nuclear test sequence involved reactor startup and temperature stabilization at our design point of 800°C (approximately 1075 Kelvin), followed by steady-state power production operation.

Subsequently, we executed a series of transient testing scenarios to evaluate system response under various operational contingencies: Stirling engine failure modes, heat pipe malfunctions, and total cooling loss scenarios. Throughout these tests, we demonstrated the reactor's intrinsic load-following capability—a critical feature wherein the reactor self-regulates without active nuclear control mechanisms, responding instead to variations in power draw from the Stirling engines.

This extensive test campaign, spanning approximately 28 hours, successfully validated all design parameters and operational characteristics. Upon completion, we had acquired the complete dataset necessary to qualify this technology for potential space deployment, should NASA choose to proceed. The Kilopower project thus achieved its objectives within both the projected timeline and budget parameters we had established with NASA.

Now at SpaceNukes, you're working on reactor designs for NASA and the Space Force. What are the unique engineering challenges in designing nuclear reactors specifically for space applications?

Upon completion of the Kilopower demonstration, we anticipated NASA would progress toward flight implementation. The technology had a strong advocate in Steve Jurczyk, who headed the Space Technology Mission Directorate and supported orbital deployment. Unfortunately, his subsequent reassignment to another senior position within NASA left the project without its key champion.

Within a year following the successful KRUSTY test, NASA's priorities had shifted, and their interest in deploying Kilopower diminished. Confronting this development, we approached Los Alamos National Laboratory about institutional sponsorship for further development, suggesting the laboratory itself could advance the technology independently of NASA. After deliberation, laboratory leadership declined, citing concerns about allocating political capital to this initiative given their primary nuclear weapons mission. However, they were supportive of our pursuing the technology through private channels and offered to facilitate licensing of the intellectual property, which the laboratory had patented.

This led to our formation of Space Nukes—the Space Nuclear Power Corporation—in 2019, though operations didn't fully commence until 2020. The origin of our company name reflects our heritage: Dave Poston, our chief reactor designer, had captained a Los Alamos softball team called 'Space Nukes' for 25 years, providing a natural identity for our new venture.

A pivotal development in establishing the company came through Andy Phelps, a former Los Alamos associate director who had spent over four decades with the engineering corporation Bechtel. Having maintained a residence in Los Alamos from his time at the laboratory, he initially engaged with us as an advisor on business formation. As the project's potential became evident, we persuaded him to assume the role of CEO and drive the commercialization effort. His commitment to the mission—what I sometimes characterize as 'drinking the Kool-Aid'—proved transformative.

By 2020, our founding team was complete: Andy Phelps as CEO, Dave Poston as chief reactor designer, myself managing company operations and regulatory affairs, and Marc Gibson, who had transitioned from NASA to become our power conversion specialist. This core team established Space Nukes with the mission of bringing space reactor technology to practical deployment.

Partnership with Space Force

Our central challenge then became identifying potential customers interested in deploying reactor technology in space. We reapproached NASA, but they maintained their position of not pursuing Kilopower deployment.

Interestingly, the U.S. Space Force, which had recently been established from elements of the Air Force, expressed interest in our technology. We engaged extensively with the Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL) in Albuquerque—one of their four primary research centers—which indicated potential interest in space reactor deployment. While these discussions generated conceptual alignment, funding remained elusive.

Fortunately, our CEO Andy Phelps had served as a White House Fellow during the Bush administration, providing him with valuable connections in government circles. Leveraging these relationships, we initiated efforts to secure congressional appropriations for the Space Force, directed toward the Air Force Research Laboratory, to support a Kilopower-derived space reactor demonstration.

This advocacy culminated in a $70 million allocation to the Space Force budget in 2022. Subsequently, AFRL established the Jetson program, with one primary objective being the deployment of a 10-kilowatt reactor in cislunar space—the region extending from Earth to beyond lunar orbit. To conceptualize this domain: if Earth were represented by a basketball and low Earth orbit by the surrounding hoop, cislunar space would encompass everything within the three-point line of a basketball court.

For this initiative, AFRL requested that we partner with an established defense contractor, resulting in our collaboration with Lockheed Martin. Our mission concept involves initial reactor activation in low lunar orbit, followed by propulsion-enabled transitions between various near-rectilinear halo orbits (NRHOs)—large elliptical trajectories with the Moon positioned at one focus. This orbital maneuvering would enable comprehensive lunar observation capabilities over approximately three years of operation.

This program represents our current flagship initiative, with our team actively designing the reactor for the Space Force application. Consistent with our naming tradition, if the previous test reactor was KRUSTY, this new system has been designated 'Cletus'—maintaining our Simpsons-inspired nomenclature.

Having worked extensively on both terrestrial and space reactor designs, how do the safety considerations and design approaches differ between these applications?

Despite superficial similarities in their utilization of fission processes, terrestrial and space reactors represent fundamentally different engineering domains. Space reactors operate in an environment requiring unique design approaches: they must reject heat through radiative transfer into the vacuum of space; they necessitate minimized mass and volume for launch feasibility; and they must function autonomously without human operators. These distinct operational parameters create fundamentally different safety considerations from their terrestrial counterparts.

Earlier in my career, I specialized in severe accident research—analyzing scenarios like those that manifested at Three Mile Island and later at Fukushima. This work centered on public safety in populated regions. Space applications present a different paradigm, as most deployment scenarios (with potential exceptions for lunar or Martian surface operations) involve minimal proximity to human populations.

Our safety philosophy for space reactors encompasses two principal strategies:

First, we implement multiple redundant measures to ensure the reactor remains subcritical during all pre-deployment phases. A significant design consideration involves ensuring that, unlike many conventional reactor designs that would achieve criticality if immersed in water, our space systems are engineered to remain subcritical even in ocean immersion scenarios. This is crucial because while unfissioned uranium presents relatively modest radiological hazards, activation products generated during operation pose substantially greater risks.

Second, we establish deployment and disposal protocols that preclude any possibility of the reactor returning to Earth's biosphere after activation. For instance, our Jetson mission architecture positions the reactor in lunar orbit with a designated end-of-life disposal trajectory that permanently eliminates any Earth re-entry scenarios. Surface deployments on other planetary bodies inherently provide this isolation.

Additionally, we engineer our space reactors with autonomous control capabilities governed by fundamental physics principles rather than active intervention systems. The KRUSTY demonstration validated this approach, confirming that reactors can self-regulate through inherent feedback mechanisms without requiring real-time command inputs—essential given communication delays ranging from seconds for lunar missions to minutes for Mars operations and beyond for deep space applications.

These systems must operate reliably for decades without maintenance or refueling, necessitating design approaches that prioritize longevity and self-regulation. The engineering solutions required for these constraints often diverge significantly from economically optimized terrestrial designs, resulting in space and Earth-based systems that share fewer commonalities than might initially be assumed.

The 2019 Richard P. Feynman Innovation Prize recognized your contributions to nuclear engineering. Looking ahead, what innovations do you believe are most crucial for advancing space nuclear power in the next decade?

Our current strategic focus balances near-term implementation with long-range technology advancement. We've developed a family of Kilopower-derived reactors that we're preparing for deployment across various mission profiles—from deep space scientific exploration to planetary surface operations—leveraging technology that's presently mature and deployment-ready.

Looking toward future capabilities, historical research dating back to the 1970s has consistently identified the need for higher operating temperatures to enable more powerful space reactor systems. The fundamental constraint involves heat rejection in the space environment. Since radiative heat transfer scales with temperature to the fourth power, achieving higher operating temperatures dramatically increases the heat rejection capacity per unit area of radiator surface. This relationship is critical for developing systems in the hundreds of kilowatts to megawatts range without requiring impractically large radiator arrays.

Powering a Habitat on Mars with Kilopower

This technological direction has been well understood for decades, but implementation requires advances in materials science and engineering to support these elevated temperatures reliably. As we progress in these areas, we anticipate significant expansion in space nuclear capabilities, enabling transformative applications across multiple domains.

For example, establishing a sustainable human presence on Mars with thousands of inhabitants would necessitate megawatt-scale power generation for life support, resource utilization, and fuel production. Similarly, we're collaborating with Dr. Franklin Chang-Diaz on his VASIMR propulsion technology, which requires substantial power inputs to operate plasma thrusters capable of efficiently transporting large cargo volumes to Mars and beyond.

Our approach is therefore two-pronged: near-term deployment of proven technology while simultaneously advancing the materials science and engineering foundations needed for next-generation, higher-power systems. This balanced strategy maximizes immediate impact while establishing the technological foundation for increasingly ambitious future capabilities.

We actively encourage public engagement with space nuclear technology. Our mission extends beyond technical development to include building awareness and enthusiasm for this field where the United States can demonstrate significant leadership. It's worth noting that international competition in this domain is accelerating—if we don't advance these capabilities, other nations certainly will.

About Patrick McClure

PATRICK MCCLURE is the Chief Operations Officer (COO) for Space Nuclear Power Corporation (SpaceNukes) and a Nuclear Engineering Consultant with over 35 years of engineering experience in nuclear reactor design and nuclear safety analysis for large reactors, micro-reactors, and space reactors. His most important contribution to the field of nuclear engineering was being the Los Alamos National Laboratory lead for the Kilopower project. Kilopower was a project to design, build, and test the first novel reactor concept in decades. His accomplishments on Kilopower include the development of a novel process that allowed for the project to successfully navigate past substantial political and safety barriers.

Mr. McClure was a senior manager and researcher at LANL for 27 years and a senior engineer at SAIC for 6 years before helping to found SpaceNukes in 2019. He has a B.S. from the University of Oklahoma and an M.S. from the University of New Mexico.

For more information, get in touch with Patrick at mcclure@spacenukes.com