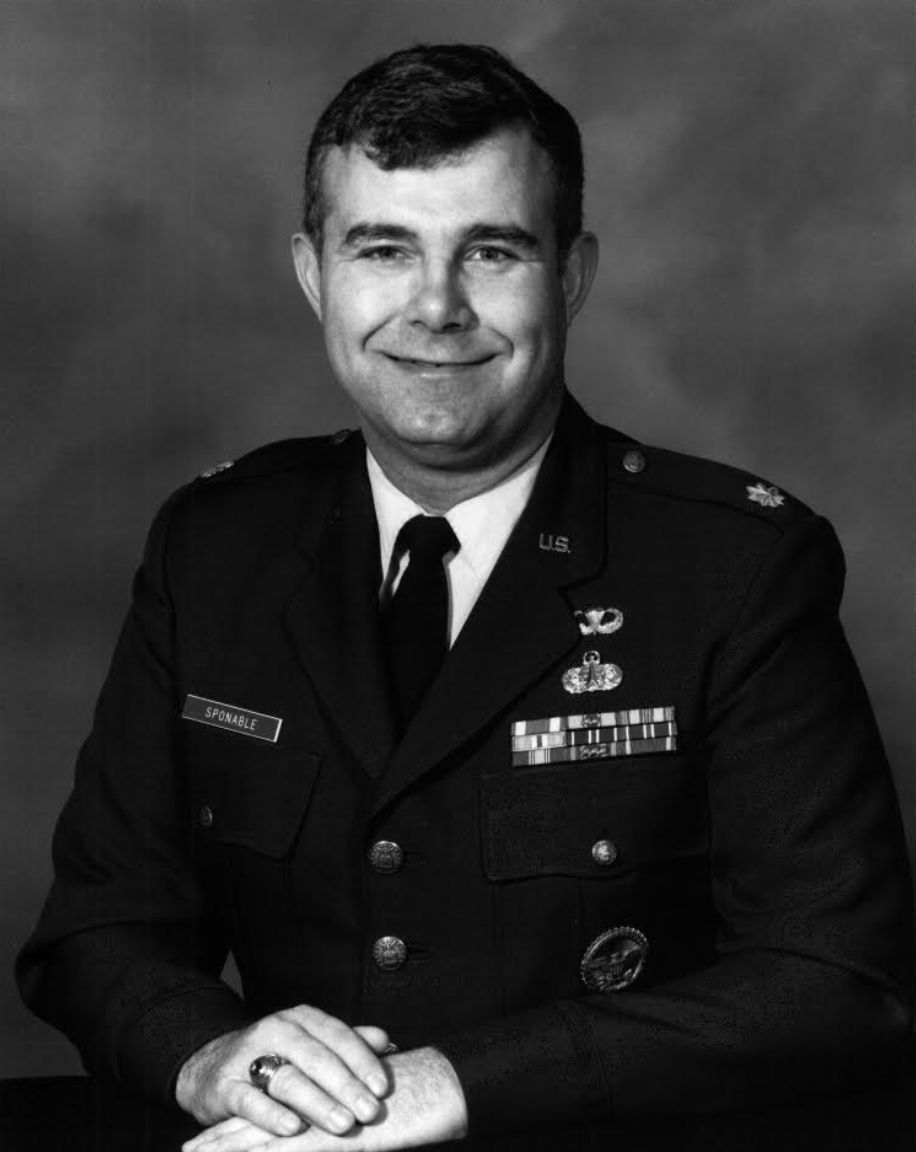

"We Can Fly 8,000 Miles In 2 Hours": Ex-DARPA PM & President of NFA, Jess Sponable, on Making Hypersonic Travel Mainstream

Aerospace pioneer Jess Sponable discusses how New Frontier Aerospace is revolutionizing global travel through rocket-powered aircraft, drawing from his extensive experience with DC-X, DARPA, and GPS development to make hypersonic flight accessible and cost-effective.

From launching early GPS satellites to pioneering reusable rocket technology with the experimental DC-X vertical lander, Jess Sponable has spent four decades pushing the boundaries of what's possible in aerospace. Now, as President and CTO of New Frontier Aerospace (NFA), he's pursuing what might be his most ambitious vision yet: enabling commercial flights to anywhere on Earth within two hours using hypersonic rocket-powered aircraft.

After twenty years in the active duty Air Force, nine years at the Air Force Research Laboratory and seven years managing breakthrough programs at DARPA, Sponable brings a unique perspective to the emerging high speed travel industry. While others chase complex turboramjet and scramjet solutions, NFA is taking a simpler approach with small, reusable rocket engines that can revolutionize both military and civilian transportation. In this conversation, Sponable reveals why rocket-powered aircraft are easier to build and far better than most think, shares lessons from working with space entrepreneurs like Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos, and explains how the commercial space industry could be approaching a historic "takeoff point" similar to the explosive growth of historic frontier cities.

You've been involved with groundbreaking projects like the DC-X and the X-40. How do these early experiences with reusable vehicle development inform NFA's approach to creating aircraft that can fly anywhere in the world within two hours?

Sponable began the discussion by reflecting on his early career choices. “From the time I was a high school student many decades ago, I was enthralled by science fiction, physics, and math—determined to figure out how we could migrate humanity throughout the solar system. I ended up going to the Air Force Academy, which laid the foundation for my career in space and astronautics. Much later in my career, I spent time at DARPA, which does a lot of amazing, advanced technology work, but it’s high-risk technology research. The way you get money for government research isn’t the same as the way you find money in the venture world,” he explains.

At DARPA, where approximately 100 program managers oversee the allocation of $3 billion annually, the mission is expansive: “Its job is really to reach out and uncover new technologies and approaches that can change how we do warfare. They address the Army, Navy, Marines, Air Force, and now the Space Force as well, so all of that is part of their portfolio.” Venture programs, however, operate differently—there are many funds, each with numerous investments, and it only takes one unicorn investment to make a fund profitable.

Sponable highlights a key philosophical difference between DARPA and commercial development: “At DARPA, you really want to be pushing the edge of technology, or they’re not interested in doing it—which is a little silly because there are a lot of things that don’t need to push the edge of technology but could still radically revolutionize both warfare and commerce.”

During his time at DARPA, Sponable worked on cutting-edge projects like “on-orbit solar electric propulsion systems” and an experimental spaceplane designed for vertical takeoff and horizontal landing. His experience with the Vertical Takeoff & Landing (VTOL) DC-X, as well as the DARPA spaceplane, led to a crucial insight about reusable rocket-powered vehicles: “When comparing vertical and horizontal landing vehicles, the defense industry consistently insisted, ‘Oh, it’s six of one, half a dozen of the other.’ DARPA proved this is not true! Reusable VTOL rockets have tremendous physics advantages over any other mode of flying to space.”

This lesson has directly influenced NFA's current approach. “Our hypersonic vehicles use technology that is simple, available, emphasizes safety, and takes advantage of the physics of high-speed flight. Instead of complex air-breathing aircraft that rival the size of a football field, we use much smaller rocket-powered aircraft flying at the top of the stratosphere.” To begin moving in that direction, NFA has developed a small liquid rocket engine, only 23 inches tall, with up to 3,000 pounds of thrust. “We call it Mjölnir, after Thor’s hammer. You can place one engine on an orbital transfer vehicle and fly from low Earth orbit to anywhere in cislunar space. Or you can install three engines on a delta-wing aircraft, like the old X-24, and fly up to 2,000 miles at hypersonic speeds.”

MACH TB 2.0 Task 3 - Accelerating Hypersonic Test with the New Frontier Aerospace Pathfinder UAS 720

The advantages of VTOL rockets are staggering, explaining the billions in private investments in reusable space access vehicles by SpaceX, Blue Origin, Rocket Lab, Stoke Space, and Relativity Space. Sponable points out, “Today’s liquid oxygen and natural gas engines are twenty times lighter than modern turbojets, have a hundred times fewer parts, and are eco-friendly with a path to carbon-neutral operations. When installed on reusable vehicles, propellant costs are up to ten times lower than jet fuel, with airframe dry weights ten times less than conventional aircraft with similar payloads.”

At NFA, they’re leveraging these advantages with a practical and near-term approach, focusing on “very small aircraft that can fly over transcontinental and, someday, intercontinental distances. We never leave the atmosphere, and we cruise using a throttled-down rocket. It’s very, very simple compared to the much larger and more complex horizontal takeoff and landing aircraft using unproven multi-mode propulsion engines. Essentially, by ignoring ‘conventional wisdom,’ we take advantage of rocket and high-speed flight physics to fly farther, faster, and at much lower cost than other high-speed aircraft concepts.”

Your work with Universal Space Lines under Pete Conrad focused on commercializing vertical takeoff and landing capabilities. How has the commercial space landscape changed since then, and what lessons from that era are particularly relevant to NFA's mission today?

Sponable's commercial space journey began during his time at the Strategic Defense Initiative Organization (SDIO), nicknamed "Star Wars" by the press. “Although I was on the Atlas launch crew for four of the first six GPS satellites, I really started my reusable launch career when I went to SDIO. I spent three years there, and although I had many jobs, my main project was flying the DC-X.”

Even then, “we had a number of commercial companies trying to introduce new launch capabilities. Orbital Sciences was one of the early ones, developing the Pegasus launch vehicle, and I managed a launch contract with them.” However, the fundamental challenge at that time was funding: “There wasn’t really much commercial money in space launch. Everybody was looking for a government contract or handout to develop something.”

The landscape today is vastly different. “There’s a lot of commercial money in these ventures now, and SpaceX in particular has done a phenomenal job building a company that has radically changed the space industry.”

Sponable recalls his early interactions with Elon Musk: “Around 2004, I met Elon for the first time. He cornered me on the shop floor of his small El Segundo facility. I think he just wanted a reality check on his decision to pursue the rocket-powered Falcon vehicle versus advanced technology turboramjets and scramjets. But I quickly realized he didn’t need my advice. He rattled off all the reasons why the Falcon approach was better—lower dynamic pressure, less aerothermal heating, lighter weights, simpler control systems. I was amazed. Unlike most CEOs of venture firms, he had a deep understanding not just of his own system but of potentially competitive concepts.”

“The only place he raised my eyebrows was his plan for reusability. He planned to fly his aluminum Falcon first stage to Mach 12, deploy a parachute, and drop it into saltwater for recovery. I told him that was not the best path to reusability. Years later, around 2014, when I was at DARPA, he called me up and said, ‘Jess, we’ve decided to land vertically like you did with DC-X. Can you send me all your data?’ So we did. We sent him and other companies several gigabytes of data. I’m not sure they needed the data as much as the validation that rockets could be landed vertically. In any case, SpaceX accelerated ahead—way beyond anything I could have imagined.”

Alongside SpaceX, the rocket-powered VTOL community has grown remarkably, with multiple companies pursuing new concepts. “We also sent DC-X data to Blue Origin and helped them where we could. Stoke Space is coming along nicely with a VTOL system that reenters base-first instead of nose-first. Rocket Lab also has a great vehicle sized for medium versus heavy-lift payloads.”

The scale of investment in the industry has grown enormously. “When you look at the capitalization of these companies, it’s in the billions of dollars. It’s a thriving community, and I hope they all survive as they traverse the ‘valley of death.’ Competition is good—the more competition we can get, the better off we’ll be. Unfortunately, some won’t survive, and I don’t have high hopes for companies still trying to build expendable launch vehicles. Even among reusable launch companies, not all will make it, but they’re doing a great job introducing an innovative generation of reusable launch vehicles. Ultimately, this new generation will bring the cost of space access down to something akin to international air travel.”

Having worked on both early GPS satellite launches and hypersonic flight systems, you've seen the evolution of aerospace technology from multiple perspectives. What developments in the next 5-10 years do you think will be most critical for enabling regular point-to-point rocket travel?

Sponable begins with a revealing story from his early work on the Global Positioning System: “I was a young officer—my hair was brown back then—launching NAVSTAR 3, 4, 5, and 6. Then I left to get reeducated at the Air Force Institute of Technology, picked up some advanced degrees, and came back as a manned spaceflight engineer, joining the GPS program at a pivotal moment. I helped develop the first block of 28 operational spacecraft.”

He recalls an early demonstration of GPS technology: “We had an Army man-pack. It weighed about 40 pounds, and they brought this demo out to show us in the quadrangle at Space and Missile Systems Center. At the time, you could get your position within three meters, but with a limited constellation, it only worked at certain times of the day.”

The GPS program was unique in both its military applications and commercial potential. “We all knew there were commercial applications, but none of us anticipated the orders of magnitude and the speed of change that would come from commercially available navigation—everything from what’s on your cell phone today to what’s in your car, plus countless industrial and lifesaving applications.”

This experience shapes his perspective on reusable launch and hypersonic flight: “I believe there’s a strong analogy between GPS and today’s reusable launch and hypersonic flight. Most people, including experts, neither anticipate nor understand emerging technology. Venture capitalists especially often misunderstand the technology and consistently underestimate who will succeed and with which innovations.”

Conventional wisdom, he argues, often gets things backward. “People say rocket science is hard, but high-speed turboramjets are easy. It’s actually the opposite. Turboramjets and scramjets are far more complex than rockets, especially because they add extra complexity at the vehicle level. A typical rocket like Mjölnir has a hundred times fewer parts than a comparable turbojet at the same thrust—it’s one-twentieth the weight. If you can make rocket-powered vehicles operate with the safety and reliability of aircraft, they could eventually cost less than subsonic jets.”

Sponable warns against relying too much on so-called experts: “I have this interesting chart I show in presentations, with quotes like the U.S. National Academy of Sciences in 1940 saying, ‘The gas turbine could hardly be considered a feasible application to airplanes,’ or a few years later, the chairman of IBM saying, ‘I think there is a world market for maybe five computers.’ And perhaps the most egregious, Bill Gates saying, ‘640K ought to be enough for anybody.’ You’ve got to be careful with experts in any field—they’re often only specialists in a narrow sense and may not understand all the system trades, especially if the approach is unconventional.”

He also notes the interplay between venture capital and government programs: “The good thing about venture capital is that many firms pick different solutions, and some of those will succeed—even though many will fail. In government programs, we tend to pick one solution and bet everything on it, which is only slightly more likely to succeed than any one of the many venture picks.”

Finally, he describes NFA’s specific approach—now with an even more ambitious long-term vision: “We’re recovering our vehicle. We take off vertically, cruise, then rotate and land vertically—a bit like Starship, which is similar to what DC-X demonstrated in the mid-1990s. With a scaled-up design, we can eventually extend our range to over 8,000 miles within a two-hour flight, which obviously has huge commercial and military implications.”

What do you think the public should know about upcoming developments in space, and what's not being discussed enough?

Sponable emphasizes a fundamental shift in space programs: “We've had a big government-run space program for years, making incremental steps and putting footprints on the Moon. Today, everything is changing as the private sector ramps up. In fact, since 2014, the cost of launch has already dropped by over an order of magnitude to between $1,000 and $2,000 per pound.”

He points to SpaceX as an example: “The goal for Starship—and others will follow—is to get under $100 per pound of payload to low Earth orbit. Musk has a personal goal to bring that down another order of magnitude. It’s not easy, but I’ve gone through the numbers on propellant and hardware costs, and it’s possible.”

He likens the economic potential to historical booms: “When costs get that low, it opens a huge opportunity on the space frontier. Take asteroids, some of which contain trillions of dollars’ worth of mineral wealth. Can we get to them affordably right now? No, but we’re approaching that tipping point. In geography, there’s something called a takeoff point—for example, a trading city might remain tiny for centuries and then explode into a massive metropolis almost overnight. That’s what I see coming in space as launch costs drop precipitously.”

Sponable believes regulation and government involvement must be balanced: “We have to get the regulatory environment right. You don’t want to overregulate and kill commercial prospects. But the government also needs to encourage and purchase flight services so that the private sector invests and companies follow through in delivering competitive flight vehicles.”

He underscores that space isn’t just about asteroid mining: “At New Frontier Aerospace, we’re not even going to orbit. But if we can fly anywhere on Earth in two hours and link the U.S. with all of Asia and Europe, it changes everything and brings the world closer together.”

He continues: “I didn’t realize this kind of flight mode was even possible until a brilliant friend of mine ran thousands of high-fidelity flight simulations. Bob O’Leary recently passed on, but he convinced me that hypersonic flight isn’t as simple as basic aerodynamics 101 would suggest. At those speeds, the physics is non-intuitive—you can fly much farther when you borrow some of the energy from gravity.”

Military applications are inevitable, though he keeps the focus on the commercial side: “The ability to get anywhere quickly is obviously attractive for defense, but that’s not what we’re talking about today.”

Looking ahead, Sponable sees real and imminent progress: “For the first time since Apollo, we’re positioned to put hardware on the Moon and Mars within the next few years. Years ago, I wrote an op-ed arguing that space launch doesn’t need ever more advanced technology—what we need is to routinely fly reusable rocket-powered vehicles with aircraft-like operability and costs. If we can rally together to incentivize the industry, success will be assured. One of the best things about space, historically, is that it used to be a bipartisan push. I worry that the modern insanity—on both sides—makes it harder to find the common-sense bipartisanship we need to truly open the space frontier to everyone.”

He finishes on an optimistic note for these efforts: “If we keep pushing on reusability and ever-lower flight costs, we’ll get rocket-powered flight that can potentially reach space or travel around the globe at costs lower than today’s long-range subsonic jets—perhaps surpassing 8,000 miles in under two hours. That’s exciting.”

Further Reading From Jess Sponable

The Physics and Future of VTOL Rockets (2024)

Following the High Speed Aerospace Transportation workshop, Sponable outlines how VTOL rockets could revolutionize transportation through their significant advantages in weight, simplicity, and cost-effectiveness compared to traditional jets. He draws parallels between SpaceX's Starship landing maneuver and similar techniques demonstrated by DC-X three decades earlier.

Read his full commentary here.

A Boost For Military Spaceplanes (2018)

In this Aviation Week piece, Sponable argues that SpaceX's successful Falcon Heavy launch and booster recovery should catalyze the Air Force to reconsider spaceplanes. He outlines how smaller military vehicles could provide rapid global reach for reconnaissance and presence, drawing parallels to the SR-71 fleet while offering greater capabilities.

The Next Century of Flight (2019)

Writing for Aviation Week, Sponable emphasizes that America needs operational efficiency over new technology in space launch. He draws from his experience with DC-X to argue that demonstrating reliable, low-cost operations is key to attracting commercial investment in reusable launch vehicles.

How to Seize Revolution in Hypersonics and Space (2018)

In this piece by Newt Gingrich with input from Sponable, they propose a three-part strategy: programmatic investment in spaceplanes, political support through state-level engagement, and economic incentives for private sector participation. The article emphasizes bipartisan cooperation as essential for advancing American space capabilities.

About Jess Sponable

Jess is the President and Chief Technology Officer for New Frontier Aerospace (NFA), Inc (www.nfaero.com). NFA is currently testing a new class of full flow staged combustion (FFSC) rocket engine with the reliability and safety features of jet engines. Key NFA products include advanced FFSC rocket engines, high ops tempo orbital maneuvering/vehicles, and high-speed point-to-point aircraft that fly at up to Mach 9 enabling two-hour flights to everywhere. With a wide-ranging background in industry and government, Jess has extensive experience developing space, hypersonic, and reusable space launch systems and technologies. In November 2017 he left the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency where he served over two separate tours and seven years as a program manager. He led multiple space initiatives including the experimental spaceplane, high power solar electric propulsion, autonomous robotic arm, and solar thermal propulsion programs. With a combined budget of over $400 million and 50+ contracts, his efforts included technology maturation of satellite projects, power systems, solar cells, rocket engines, electric propulsion, and space launch. Prior to DARPA he spent over 30 years in the United States Air Force as both a military officer and civilian. His career supported diverse jobs ranging from Atlas launch operations at Vandenberg AFB to project management jobs developing and deploying the early Global Positioning System. Prior to the Space Shuttle Challenger accident, he was selected as an Air Force Manned Spaceflight Engineer and trained as a Space Shuttle payload specialist, then transitioned to support development of hypersonic flight at the National Aero-Space Plane program. Starting in 1991 he served in the Strategic Defense Initiative Organization managing multiple programs including the vertical take-off and landing Delta Clipper-Experimental (DC-X), which inspired many follow-on entrepreneurs. In 1994 he transitioned to the Air Force Research Laboratory supporting NASA’s follow-on initiatives DC-XA, X-33, X-34, and related technologies. In the Air Force he led or supported numerous projects and studies maturing hypersonic aircraft, orbit transfer vehicles, reusable space launch/military spaceplanes, and prompt global strike systems. Jess also spent several years in the entrepreneurial space launch sector working for Universal Space Lines and Pete Conrad, the Apollo 12 and Skylab commander. He has served on numerous national space transportation studies and panels. He is a graduate of the Air Force Academy with a bachelor’s degree in physics and holds advanced degrees in Astronautical Engineering and Systems Management. He is a graduate of the Defense Systems Management College.