"First Day on the Job, Hubble Was Broken:" James Webb Space Telescope Pioneer Mike Kaplan on Crisis, Innovation, & Space's Commercial Revolution

Mike Kaplan shares his journey from NASA's Hubble crisis to pioneering JWST, and how the space industry transformed from government-led programs to commercial innovation.

"Hubble Mirror Flawed," read the Washington Post headline on Mike Kaplan's first morning as NASA's new "scope guy." It was 1990, and he'd just been hired to plan America's next great space telescopes to follow the Hubble Space Telescope. As his wife wryly noted, "looks like the market demand for your business just took a nosedive this morning."

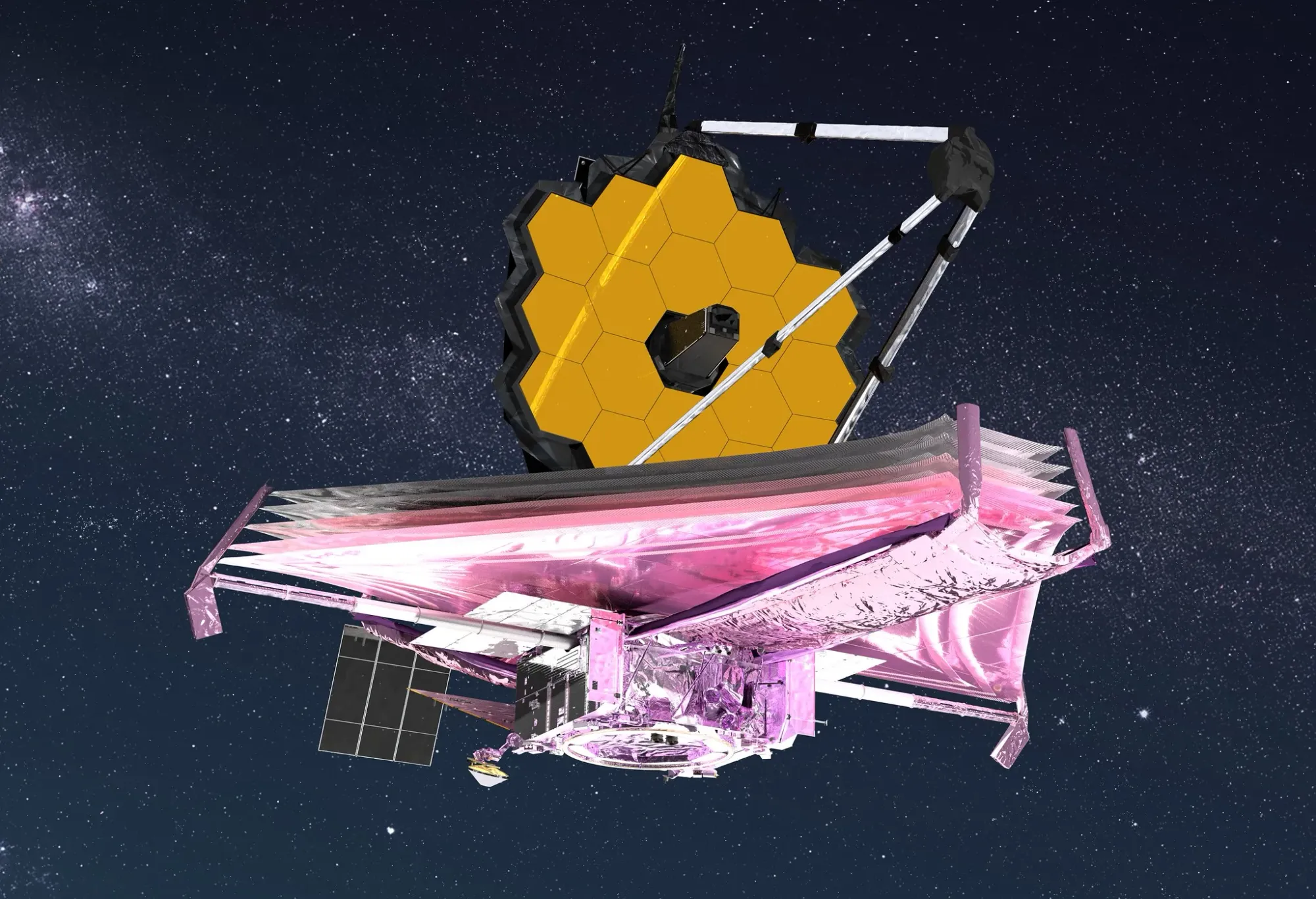

That crisis would spark a revolution. Over the next decade, Kaplan would help conceive and champion what became the James Webb Space Telescope—breaking the fundamental rules of telescope design by splitting its massive mirror into segments and pushing the boundaries of what was possible in space. It was a watershed moment that would transform our view of the universe.

Yet that wasn't the last time Kaplan would help remake the space industry. After leading teams at NASA, Boeing, and Ball Aerospace on some of space's most ambitious projects, he found himself at the center of an even more significant transformation: the complete reinvention of space business. With over $15 billion in successful space business across both government and commercial space, Kaplan has uniquely straddled the divide between "Legacy Space"—where performance was everything—and today's "New Space" revolution, where the rules have been completely rewritten.

"It's mind-bending for folks that have come up in Legacy Space," Kaplan explains. "What the customer cares about has been flipped upside down. You have to literally reprogram your brain and think about the problem in an entirely different way. Some people can do that, and others can't."

In this conversation, Kaplan reveals how the fundamentals of space business have been and are still being transformed and why the relationship between government and commercial space may be far more complex than anyone expects.

You've worked on transformative projects like the James Webb Space Telescope from its early days. Looking at today's space economy, what emerging technologies or missions do you believe will have a similar watershed impact on space exploration?

"Webb came at a really unique time," Kaplan explains. "I was lucky enough—my first day at NASA headquarters coincided with what the astronomy community calls ‘Spherical Aberration Day.” I was about to drive to headquarters, and like everyone else in the DC area, I opened the Washington Post and saw 'Hubble mirror, flawed.' I thought, 'I'm NASA’s new telescope guy, right?' I was hired to plan what comes next. And as my wife said at the time, 'Looks like the market demand for your business just took a nosedive this morning.'"

He was involved peripherally on the Hubble repair mission, which taught him valuable lessons. "We were fortunate that Hubble was designed from day one to be serviced and upgraded—it was launched on the Shuttle, and the Shuttle was planned to service Hubble fly every few years to upgrade the telescope’s instruments and replace or replace key spacecraft subsystems."

Kaplan explains that in space science—including planetary science, heliophysics, and, to a lesser extent, Earth science—increasing performance incrementally wasn’t enough. "It costs a lot to go into space to conduct scientific research, so for each new next mission, we need to make significant leaps forward. In other genres like military or commercial applications, people are happy with a 10% or 20% improvement in some KPI—say, better sensitivity or low-light performance. In astronomy, you must achieve an order of magnitude leap in something, whether spatial resolution, spectral resolution, or sensitivity. The history of astronomy has shown with great leaps forward in observational power bring significant advances in human understanding."

At the time, NASA’s new Administrator, Dan Goldin, had challenged space scientists to embrace "smaller, faster, cheaper" missions in planetary science to make more rapid scientific progress. The challenge with Webb was fundamentally different. "In astronomy, you can't simply go smaller and still explore the edge of the universe. You need to use larger telescopes to explore ever deeper ," he notes. "We needed a larger aperture, but the width of existing launch vehicles constrained our thinking."

Dan Goldin challenged NASA’s leaders to embrace new technologies more aggressively. For astronomy, this required a different approach. "The challenge with Webb was breaking the paradigm of a single piece of glass. I use 'glass' in quotes because Webb’s optical systems ended up being made of beryllium, but it took time to determine the best material and to figure out how best to break it into many pieces."

"The actual aperture size was originally eight meters, and it was de-scoped down to 6.5 meters after I left NASA," Kaplan recalls. "Since the driving science requirement was to look for baby galaxies, you had to look back in time to around 100,000 years after the Big Bang. To do this, you had to observe in the infrared because the universe is expanding. Light is red-shifted as one observes deeper space towards the universe's beginning."

This created additional challenges. "When you observe in the infrared, the telescope needs to be really cold. We’re talking about around 400 degrees Fahrenheit. NASA’s earlier infrared telescopes were cooled by flying inside a big thermos bottle. But building a 'thermos' that’s six or eight meters in diameter is really hard. We decided that the best way to cool Webb was to move it far away from the Earth and the Moon – major heat sources – and then hide the telescope behind a big sunshade. We settled on locating Webb at a spot called L2."

Kaplan played a pivotal role. "I was the one at NASA headquarters who essentially started it all, framed what we call in engineering the initial conditions of the problem, and then brought the team together. We hired the smartest optical designers, materials specialists, deployment experts, etc."

He acknowledges one significant oversight. "The one mistake we made was that I wasn’t aware of what was happening at DARPA. They were planning what later became the Orbital Express program, the first satellite servicing demo mission that used robotics to service another satellite with humans... We might have explored making James Webb robotically serviceable if I had known that DARPA was developing this robotic satellite servicing technology."

Kaplan sees several transformational technologies and capabilities that are currently reshaping the landscape in space today. These include:

- Robotic Servicing:

"We're seeing many commercial companies developing satellite servicing solutions, and those solutions have what I call a high 'technology dot product' with several other market adjacencies including orbital transfer vehicles, satellite refueling, and orbital debris removal satellites. A mission that can refuel a satellite, deorbit it, or manage orbital debris—many of the basic building blocks are largely the same; it’s just the application software that changes." - Orbital Transfer Vehicles (OTVs):

"Think of it like when Airbus announced the launch of their new product, the A380—a ginormous plane. No one wants to stay at the airport; people have different destinations. So, what do they do? They rely on services like Uber or Lyft. In much the same way, passengers on these new emerging large launch systems will want OTVs to get them to their final destinations." - Optical Inter-Satellite Links:

"We're seeing the emergence of optical inter-satellite links. A standard has been established by the Space Development Agency (SDA), and multiple companies have built these links. This technology will provide the backbone for space communications." - Edge Computing in Space:

"As satellites become more capable and can provide more power, we will see a surge in onboard processing. There won’t even be a need to beam data down to the ground for processing. Essentially, the cloud is moving to orbit. More and more processing will be done on the satellites." - Small Geostationary Orbit Satellites:

"The price points for small GEO satellites are significantly lower when compared to legacy space school bus-sized satellites. And we know that business cases that wouldn't otherwise close start to become viable whenever you drop the price of something—whether in launch or satellites."

He also highlights the influence of the SDA. "They are acquiring hundreds of satellites a year. They’re awarding a couple of billion dollars in contracts for this satellite class annually. These actions are driving the satellite manufacturing market."

Having successfully transitioned from 'Legacy Space' to 'New Space', what key differences have you observed in how these two sectors approach innovation and risk? How has this shaped your approach to business development?

"It's kind of mind-bending for folks who grew up in the legacy space sector," Kaplan begins. "The first thing is that what your customers want is very different. He explains the fundamental shift in evaluation criteria: "In the past, the customer's evaluation criteria were always in priority order (1) Technical Performance, (2) Schedule, (3) Reliability, and then (4) Price. Now, we live in the world of fixed-price contracts, where Price is number one, Schedule is number two, Reliability is number three, and Technical Performance is number four."

The nature of contracts has also transformed dramatically: "This is largely seen with the US government. Up until about 10 years ago, the non-commercial space business—dominated by government spending—relied on what’s known as cost-plus contracts. This means that when you bid, you cover your cost and then add a fee, typically around 10%."

This old model had specific characteristics: "Customers were constantly changing and tweaking the requirements. Whenever a requirement changed, your cost would change, leading to a contract modification, and the price would keep rising. That was the game played for about 50 years."

Kaplan notes this cost-plus model has its place: "And that's fine—in fact, the cost-plus model works well when you're trying to do something that's never been done before."

The transition to firm fixed price contracting brought new challenges: "What that means is that if you're taking a product you already have and making only minor modifications to meet the customer's needs, you're in pretty good shape. When you submit a firm-fixed-price bid, you include reserves to account for the unknown unknowns. But whenever the customer requests a change, the price increases significantly because all the assumptions you made when setting that price are now locked in. This discourages customers from frequently changing requirements in fixed-price contracts."

This shift has profound organizational implications: "Many leaders that grew up in the legacy space world struggle to succeed in this new environment. That’s because how they thought about and plan new programs is entirely different today." The transformation extends beyond engineering: "All the contracts and legal teams, along with the rest of the company's infrastructure, are now operating differently than in the past."

This mainly affects companies that aren't vertically integrated: “If you're horizontally integrated, you need to secure firm-fixed-price bids on all elements of your supply chain. Not everyone has the resources to vertically integrate like Elon Musk or Jeff Bezos, although many try to emulate that model.."

Kaplan emphasizes the fundamental nature of this change: "It’s a real brain-teaser—you have to wrap your head around how to succeed in this new world, rethink how you design a solution, and rebuild your business because the customer’s priorities have completely flipped. Those who successfully transition from legacy space to new space—let's say they undergo a mental update, even a kind of lobotomy—can free their minds and approach the problem in an entirely different way. Some people can do that; others can’t.”

With your experience on NASA's astrophysics missions and your recent work with commercial space companies, how do you see the relationship between government and commercial space evolving over the next decade?

"Originally, the space program began within the Government—largely as a reaction to the Soviets launching Sputnik," Kaplan explains. "At that time, Government engineers and organizations were built from what existed in military ICBMs. The rest had to be built from scratch because very little capability existed within the Government. Very little existed in private industry. The government developed a wealth of expertise and then hired industry, which in turn learned a great deal from the Government over the following decades."

He outlines the historical progression: "That model—where the government led and industry followed—largely remained intact. However, by the early '90s, we started to see a shift, driven in large part by the emergence of new launch providers. Several companies attempted to achieve what SpaceX ultimately accomplished. Those interested in the topic should explore some fascinating books on the history of SpaceX. They really lucked out and benefited significantly from NASA funding to get their systems into orbit."

Kaplan then describes a symbiotic relationship developing with SDA: "What SDA wanted to do was leverage existing commercial satellite bus capabilities. In Tranche 0, SDA leveraged what existed. Then, as the program progressed—consistent with a spiral development architecture SDA is using—the payload requirements increased in size, weight, and power, or SWAP. Increased payload SWAP drove satellite manufacturers to need larger solar arrays and support heavier imaging and other advanced payloads."

This government push had unexpected commercial benefits. "What ended up happening," he continues, "is that other commercial entities—whether satellite manufacturers or customers—began to say, 'Wow. I didn’t realize you could get 500 watts of continuous power from this type of bus. I thought we were limited to around 200 watts. Now I can do X, Y, and Z.' New commercial opportunities started to emerge purely due to the government challenging commercial satellite providers. Then, when Tranche 2 comes along, the satellites become even more capable. It’s a symbiotic push-pull dynamic driven by customer demand, with manufacturers investing resources to improve their products based on market needs. I believe this trend will continue."

The relationship continues to evolve. "In many ways, we've transitioned from the era of the 1990s—when the US government led and the industry followed—to a situation where the roles are much more balanced, and in many cases even reversed with industry now leading in many areas."

Regarding regulation, Kaplan sees growing complexity. "I know there's a lot of push—especially with the new administration—to remove regulations to stimulate innovation. However, if you talk to the astronomy community, you'll find they are upset about LEO constellations' proliferation. It will soon become almost impossible to conduct meaningful observations from the ground."

He emphasizes the growing challenge of orbital debris: "What about orbital debris? It is a growing problem. While we’re not yet at what’s often called the 'Kessler syndrome,' it’s clear that solving these issues and ensuring sustainability in orbit will require regulation."

Kaplan expresses concern about deregulation: "I don't think reducing regulation is the answer like many argue. Some regulations need to be improved, but one could also argue that in some cases additional regulation is needed."

He shares an illuminating example from his teaching experience: "I teach a class as an adjunct faculty at Embry-Riddle, and one of the projects involves developing an orbital debris mitigation solution. I asked the students at the beginning of the class, 'What's the toughest problem?' They all started suggesting technical solutions, but the real challenge is figuring out who gets invoiced—who's responsible for the cost. In other words, we need a viable business model to solve this problem. A regulatory framework might best address that problem."

"Maybe we need an operating model in space where everyone who puts something into orbit is taxed, and the funds go into a program dedicated to cleaning up orbital debris. We have to figure that out."

You've led teams that secured over $15B in contracts with a 75% win rate. What's your framework for identifying and pursuing the right opportunities, especially in today's increasingly competitive space market?

"Sometimes, you have the luxury to pick and choose which opportunities to pursue. Other times, you don't, and you have to make the best of a non-optimal situation," Kaplan explains. "Typically, if you're in the commercial space world— which I am, and in which I frequently discuss opportunities with customers and management—you hear many different opinions. Some say, 'We're focused on the commercial space market,' while others argue for concentrating on government contracts, the Department of Defense, or civil space."

He emphasizes that qualifying opportunities is one of the biggest challenges in the commercial space sector. "The hardest thing about commercial opportunities, as I see it, is not the sheer number available but rather qualifying them. What do I mean by qualifying opportunities? You might discuss with someone interested in buying your product—whether it's a satellite bus, a complete satellite solution, or even a payload. You go through the standard business process: exchanging non-disclosure agreements, performing technical and financial due diligence where everyone reviews the details."

Kaplan shares a recent cautionary experience: "I recently had an experience where we worked really hard for about nine months to win a commercial contract. We did everything—detailed negotiations, open-book reviews, and all the due diligence. Then, just as we were well into the program, payments stopped. Our commercial customer suddenly began struggling, and essentially, the contract died. We thought we had done an excellent job in qualifying that opportunity."

The outcome was costly. "We ended up settling to minimize our losses. It was a completely unforeseen situation."

Given these challenges, Kaplan advocates for a balanced approach. "For companies looking to enter the space business—especially here in the US—you'd be crazy not to consider pursuing US government work. I say that with some caution, though, because it's unclear what the new administration will do or what boundary conditions they'll impose. Generally, however, the US government tends to have a higher P[Go] or probability of go,' meaning a greater likelihood that the opportunity will actually materialize compared to many commercial ventures."

However, he warns against limiting oneself solely to government work. "On the other hand, if you're entirely focused on US government business, you're likely missing out on potential commercial opportunities. My general advice to companies in the new space world is to diversify and pursue both types of opportunities, as each has its own set of advantages."

He concludes with a realistic assessment of the risks: "If you can start by winning some US government business, that success can create a foundation upon which you build your company, allowing you to pursue selective commercial opportunities later. But you must work hard to qualify those commercial opportunities thoroughly—you are bound to get burned on some fraction of them, and that fraction varies depending on your situation and who you're working with. There's no easy answer. It sounds attractive because there are so many opportunities out there, but as I mentioned earlier, we thought we had done an excellent job qualifying a customer, and yet things still went awry."

About Mike Kaplan

Mike Kaplan is a thought leader in multiple space domains, with extensive experience in government (NRL and NASA HQ), industry (Ball Aerospace, Boeing, SSL/MDA, Raytheon Technologies, and LeoStella), and academia (Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University). His success spans from "Legacy Space” to “New Space,” where he has directed teams in developing new space technologies and products, including highly complex payloads, spacecraft subsystems, spacecraft buses, planetary landers, robotic satellite servicers, and complete missions from LEO to deep space across the civil, commercial, and national security sectors. He has created and secured over $15 billion in USG and commercial markets, boasting a career capture success rate of over 70%. Mike has led the creation of several transformational space missions, such as the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), the Spitzer Space Telescope, and the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA). Recently, he has focused on proliferated low Earth orbit (LEO) constellations for Earth observation/ISR, communications, and space domain awareness missions. Mike earned a BSE in Aerospace & Mechanical Sciences/Engineering Physics from Princeton University and an MS in Electrophysics from The George Washington University. He is also an Adjunct Faculty member at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, where he teaches “Space Technology & Systems" and “The Launch Industry” classes to master's students. Mike was elected an Associate Fellow of the AIAA, is a member of the Small Satellite and Space Systems Technical Committees, a Senior Member of the IEEE, and part of the Space SMART think tank. He enjoys technology, travel, hiking, and photography, and resides in Boulder, CO, with his wife, Karen Miller, and their Goldendoodle, Luke Skywalker.

For more information, contact Mike at mike@kaplanastronautics.com