"We're Being Attacked Every Day": Former Pentagon Space Advisor Christopher Stone on Why America is Losing the War in Orbit

Former Pentagon space advisor Christopher Stone reveals how America's satellites face daily attacks while China's advancing weapons threaten every major asset in orbit. Learn why our diplomatic strategy is failing and what's at stake in the hidden war above our heads.

Behind the headlines about commercial spaceflight and lunar missions lies a darker reality: America's satellites are under constant attack. "We're being attacked at a low threshold every day," warns Christopher Stone, "yet we act like it's some future problem." After decades working at the intersection of military space operations and defense policy, including serving as Special Assistant to the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Space Policy, Stone has emerged as one of the most forceful voices warning about America's vulnerabilities in orbit. As Chinese weapons now threaten "every major asset in every major orbit" and GPS jamming disrupts commercial flights, Stone argues that America's diplomatic approach has failed. While policymakers focus on "responsible behavior" in space, he sees a gathering storm - one that could leave America powerless in humanity's newest warfighting domain.

In this conversation, Stone reveals why China's "attack to deter" doctrine makes space conflict more likely than many realize, explains how America's self-imposed restrictions may be inviting aggression, and warns that without a dramatic shift in strategy, the U.S. could lose its next war before it begins - in space.

What sparked your interest in space?

"It goes back to third grade. I had a teacher who was involved in the Teacher in Space program in the mid-'80s, the same effort that ultimately sent Christa McAuliffe aboard the Challenger. Even after the accident, she remained passionate about space—both from civilian and military perspectives. As a kid, I was more focused on becoming an astronaut. I wanted to command spaceships and explore the unknown.

When I got to college, the degree programs I had hoped to pursue didn’t quite work out. Instead, I joined the Air Force and became a Space Operations Officer while still trying to stay on the astronaut path. Over time, I shifted toward operational planning and strategy, earning several graduate degrees. By 29, I had landed my first space policy-related job in D.C. By then, I had moved to the Reserve component, balancing operations on the military side with policy work on the civilian side. That dual perspective helped me understand how they interacted.

For my master’s degrees, I focused on deterrence theory because I kept hearing the terminology in the Pentagon and wanted to assess whether we were thinking about it correctly—or what we might be missing. I enrolled in a specialized D.C. program that emphasized deterrence theory, primarily in the nuclear and WMD spheres. That research led to my thesis, which became my first book, Reversing the Tao, published in 2015–2016. It’s still used in Space Force and Air Force professional education programs today.

9/11 also played a major role in shifting my mindset. Initially, I wanted to help take the flag into space. But after that day, I became more focused on ensuring we’re properly postured to protect ourselves.”

As a former Special Assistant to the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Space Policy, what changes have you observed in space deterrence strategy since China's 2007 anti-satellite test?

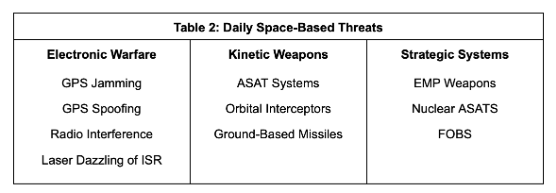

"The most significant shifts in space deterrence and warfighting have occurred on the Chinese side rather than the U.S. side. The Director of National Intelligence’s worldwide threat assessments have consistently identified China as the fastest-growing and most rapidly deploying space force in the world. Their capabilities range from reversible threats—such as jamming, spoofing, and radio interference—to kinetic interceptors capable of physically destroying satellites.

On the U.S. side, many policymakers and strategists initially assumed the issue could be mitigated through diplomatic engagement, ‘naming and shaming’ China in international forums, or promoting norms of responsible behavior. Rather than critically analyzing China’s own writings and behavior, there was a prevailing belief that integrating them into the global economy and international institutions would make them more democratic, less communist, and more cooperative on the world stage—rather than narrowly focused on their sovereign interests.

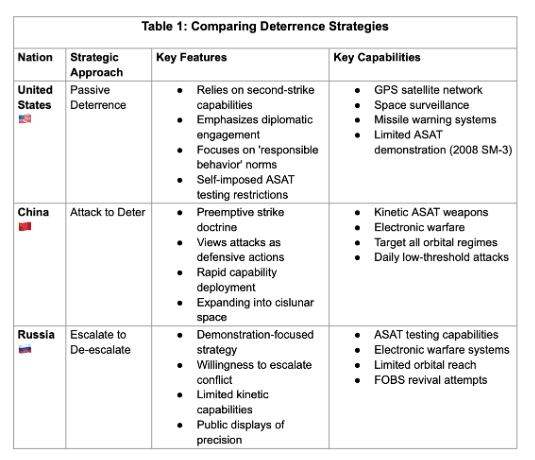

A key distinction lies in how each nation approaches deterrence. The United States and its allies typically adopt a passive stance, relying on second-strike capabilities after being attacked. In contrast, China follows an ‘attack to deter’ strategy. If they perceive a threat emerging—regardless of whether the U.S. considers it peaceful—they reserve the right to strike preemptively. To them, this is a defensive action, not an act of aggression, as we would define it.

The establishment of the U.S. Space Force in 2019, alongside U.S. Space Command as a combatant command, was intended to address these threats. However, despite extensive discussion, we haven’t meaningfully adjusted our force posture. Many in the policy sphere continue to redefine deterrence in a way that emphasizes diplomacy over military readiness. As a result, in my view, we’ve failed to establish a credible deterrent against the Chinese threat."

How does Russia's approach to deterrence compare to China's?

"While China follows an ‘attack to deter’ or active deterrence strategy, Russia employs a doctrine known as ‘escalate to de-escalate.’ The concepts are similar but framed differently. For both nations, what we refer to as ASAT ‘tests’ are actually demonstrations—signals of capability and intent directed at the U.S. and others. That’s why diplomatic protests about ‘irresponsible behavior’ have little effect. In fact, the Russians have responded to such criticism with remarks like, ‘We executed the strike with the accuracy of a precise watch.’

Both Russia and China are willing to escalate conflict to force an adversary to back down. However, there’s a key difference in capability. While Russia has limited kinetic interceptor capacity, China has demonstrated since 2014 the ability to target nearly every major asset across all key orbital regimes, from Low Earth Orbit (LEO) to Geosynchronous Orbit (GEO). More recently, they’ve begun expanding operations into cislunar space, building architectures beyond traditional orbital zones.

Russia may rely on escalation tactics similar to China’s, but China’s superior range and technological advancements make them the more formidable long-term threat."

Drawing from your experience leading the Space Operations Directorate at NGB, how do you envision integrating Space National Guard capabilities with the broader U.S. Space Force mission?

“The National Guard—particularly the Air National Guard—has supported space missions since the early 1990s, long before the Space Force was established in 2019. The Guard model is cost-effective because most personnel serve in a part-time, drilling status capacity. Unlike active-duty counterparts, they don’t receive full-time pay or benefits, yet they remain proficient in critical missions, including satellite command and control, missile warning, space surveillance, and electronic warfare operations using systems like CCS and Bounty Hunter.

This structure reflects a long-standing constitutional balance of power—both military and political—between a federally centralized warfighting service and a state-based defense force that can be federalized when needed. This dual-status framework dates back to the Army National Guard’s origins in the 1630s and the Air National Guard’s establishment in 1946.

Guard units can rapidly scale operations and deploy worldwide at a fraction of the cost required to maintain an active-duty force. While they operate under state control when not federalized, they still support federal missions, require constant readiness, and participate in national deployments. The challenge since the Space Force’s creation has been determining where these Guard units should fit within the new structure.

Congress has imposed strict limits on Space Force personnel, both uniformed and civilian, making the Guard a logical solution for supplementing manpower and capabilities. However, political friction has emerged at the federal level, with some policymakers seeking greater centralized control over these units rather than allowing them to remain under state governors and adjutant generals when not federalized.

Last year’s NDAA introduced a controversial provision that effectively bypassed existing laws and constitutional precedent, attempting to transfer these Guard units and their equipment into the Space Force. As a result, many of these units now face deactivation. This is particularly concerning given that 60% of the nation’s electromagnetic warfare assets reside within the Guard. If these units are disbanded, their personnel will not automatically transfer to active-duty Space Force; they will remain with their respective states. Rebuilding that expertise within the Air Force would take over a decade and cost significantly more than simply establishing a dedicated Space National Guard.

During his campaign, President Trump advocated for a Space National Guard as the Space Force’s primary reserve component, recognizing its proven capabilities. However, the previous administration was not supportive, and despite campaign promises, no executive orders or directives have been issued from the White House to formalize this transition.”

Your thesis focused on "Posturing American Space Deterrence for the Second Nuclear Age" - how has your perspective on space deterrence evolved given recent developments in hypersonic weapons and counter-space capabilities?

“When I first started writing about space deterrence in 2006—leading up to my 2015 book—I focused on whether U.S. posturing and strategic thinking were effectively deterring China. My goal wasn’t to predict immediate change but to gradually push the conversation in the right direction while remaining as pragmatic as possible.

In my military capacity at SAASS, I wrote a paper titled "Posturing Space Deterrence for the Second Nuclear Age." At the time, I had started seeing concerns raised in congressional hearings about North Korea potentially gaining access to Russian and Chinese information on electromagnetic pulse (EMP) weapon systems. These could be launched into space or sent on long ballistic arcs toward the U.S. mainland, detonating to cause widespread damage. While North Korea's missile capabilities were developing, its space efforts remained lackluster. Now, however, we’re witnessing a convergence of space and weapons technology across China, Russia, and North Korea, reinforcing many of the concerns I raised years ago.

My approach was to lay out the facts—their strategic thinking, their capabilities—without speculation. Even then, many faculty members and reviewers considered my perspectives out there, particularly my analysis of Chinese deterrence strategy. The common Western perception was that China sought a "peaceful rise," yet their own internal military writings explicitly stated their pursuit of space dominance. Publicly, they avoid such rhetoric to maintain a non-escalatory image, but their classified doctrine tells a different story.

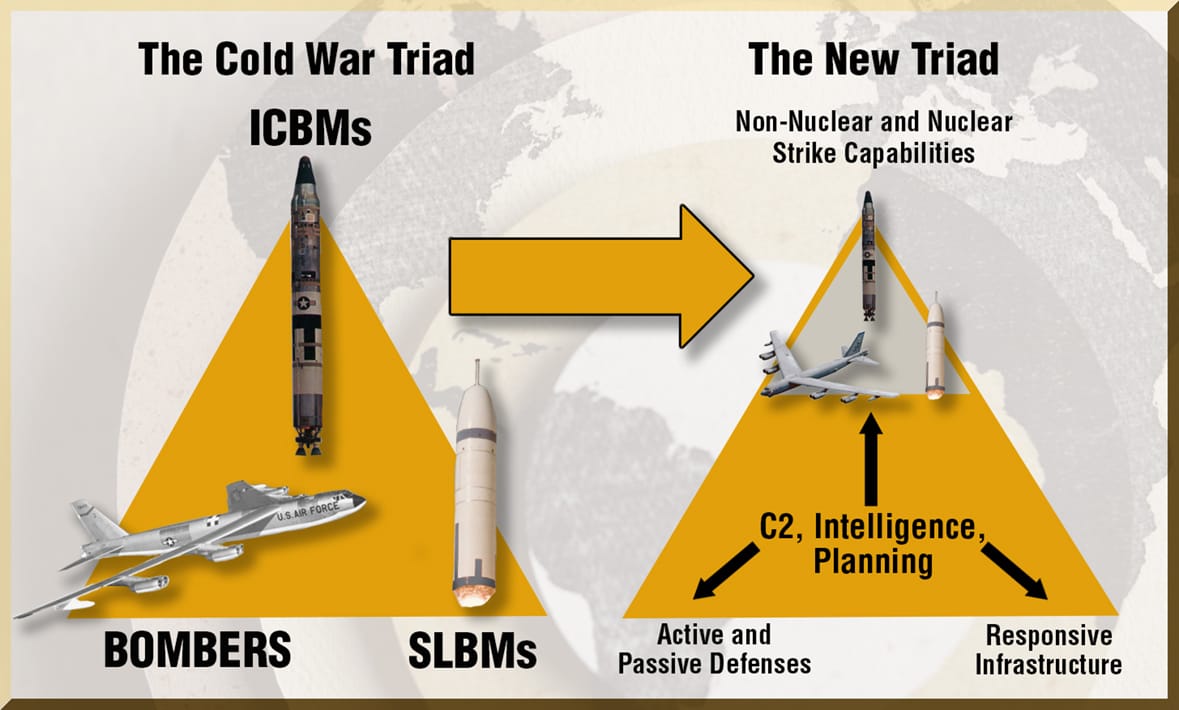

Today, nuclear anti-satellite (ASAT) weapons are returning to the conversation. I had considered including this in my original paper but chose to focus on a narrower argument for clarity. Whether it’s EMP weapons, nuclear ASATs, or similar technologies, their application depends on intent. They can be detonated near a target, used to charge the Van Allen belts to disable multiple satellites at once, or deployed as part of a Fractional Orbital Bombardment System (FOBS)—a capability China has already demonstrated and Russia is now reviving, potentially with a hypersonic glide vehicle carrying a conventional or nuclear payload.

The U.S. has not adequately postured for this kind of threat—just as it wasn’t in the late 1960s when the Soviets first introduced a similar concept. Back then, we largely ignored it, hoping it would fade away. And for a time, it did—when the Soviet Union collapsed, they lacked the resources to sustain these programs and de-orbited many systems. But with the resurgence of oil revenue and the misguided goodwill efforts the West extended in the ’90s and early 2000s, these capabilities are being revived. Instead of fostering cooperation, our outreach was leveraged against us, reinforcing Russia and China’s long-standing ambitions for global leadership and space dominance.

Whether people choose to acknowledge it or not is irrelevant. It’s a reality grounded in history—one we must confront rather than ignore."

Based on your work at the National Institute for Deterrence Studies, what are the most critical gaps in current U.S. space policy regarding commercial space integration and security?

“We've made significant progress with commercial space integration, particularly with New Space companies. SpaceX, for example, has drastically reduced launch costs compared to traditional providers like ULA. We've moved from considering six launches per year as good to executing up to 130 annually—sometimes launching six missions in a single month. The ability to send dozens of payloads on a single rocket, rather than just one large vehicle, has transformed both cost efficiency and operational tempo.

However, government acquisition processes remain a major obstacle. While there are historical reasons for the extensive layers of oversight, they often slow innovation. Organizations like the Space Development Agency have started using Other Transaction Authorities (OTAs) to accelerate development and bypass some bureaucratic bottlenecks, though challenges like lawsuits and procedural disputes still arise.

We need to shift toward a service-provider mentality when procuring space capabilities. For example, if Starship or Dragon could serve as platforms for a critical space defense system to establish space superiority—which I believe we currently lack—then we should act decisively. If a single provider has the proven capability to meet an urgent need, we shouldn't wait 10 years for competitors to catch up before awarding contracts. While competition is valuable, we’ve wasted too much time in the last two decades forcing traditional competitive processes when there’s clearly only one viable option. Let others catch up, and then expand the contract—but in the meantime, we must act.

One of our most glaring weaknesses is in space-based weapon systems. We lack the ability to effectively deter or respond to attacks—whether from low-threshold electronic warfare (e.g., jamming and spoofing) or kinetic intercepts. We’re overly concerned about debris mitigation while China, despite its public rhetoric about peaceful space development,continues to build and deploy weapons, attacking U.S. assets daily. As Vice Chief of Operations General Thompson stated, these low-level attacks occur every single day, yet we still act as if this is a future problem.

Until we acknowledge that we are already under attack and take action to reestablish deterrence, we will continue to fall behind. Effective deterrence isn’t achieved through meetings or policy papers declaring responsible behavior—it requires adversaries to perceive a credible threat, recognize our political will, and understand that we have the capability to impose costs. That means not just having the right weapon systems, but also demonstrating them.

Unless we address these gaps—particularly in monitoring adversary activity and building real deterrence capabilities—we risk losing a great power war before it even begins.”

Having served as both an academic and military space strategist, what lessons from Cold War space operations remain relevant for today's great power competition in space?

“During the Cold War, we were more willing to adapt existing programs to counter emerging threats. A prime example is the only operational anti-satellite (ASAT) weapon system ever deployed for an extended period. When several Thor intermediate-range ballistic missiles (IRBMs) were decommissioned from nuclear alert duty, they were repurposed by equipping them with small warheads and stationing them on Johnston Island in the South Pacific. From 1965 to 1975, these served as a counter to Soviet Fractional Orbital Bombardment System (FOBS) threats. However, the Ford administration later deactivated them, shifting away from nuclear interceptors in favor of conventional approaches that wouldn’t require nuclear detonations over the Pacific.

We could take a similar approach today. To establish first-strike stability against Chinese threats, we could deploy Standard Missile-3 (SM-3) interceptors, which were successfully demonstrated in 2008 when an Aegis destroyer shot down a low-flying satellite. These could be positioned either at sea or through Aegis Ashore installations to deter low-altitude EMP satellites or long-range strike assets. Similarly, the existing Ground-Based Interceptors (GBIs) in Alaska and California, designed for mid-course missile interception, could potentially extend coverage into low and medium Earth orbit (LEO/MEO). This would allow us to protect at least two of the three primary operational orbital regimes while working to deploy conventional on-orbit deterrence capabilities—remaining compliant with the Outer Space Treaty.

A common misconception is that treaties prohibit all weapons in space, which is not the case. More importantly, historical precedent shows that Russia and China have a long record of breaching or circumventing political and arms control agreements—dating back to the Hague Conventions in the 1890s. While diplomacy should always be pursued and treaties remain valuable, they are only effective when backed by credible military deterrence. Without hard power reinforcing soft power, our diplomatic efforts remain hollow and ineffective.”

What's your perspective on the recent increase in GPS spoofing incidents affecting flights, and why isn't there more public awareness about these space-based threats?

“This issue has several dimensions. First, there’s the “out of sight, out of mind” factor. Until GPS attacks—including jamming incidents affecting commercial airliners in Europe and Asia—became more publicly noticeable, most interference targeted government assets and was largely kept quiet. Officials often downplayed these events to maintain an image of stability and avoid diplomatic tensions. The prevailing mindset was that ignoring the issue might prevent adversaries from benefiting from the attention.

This mentality still exists today across multiple space-related threats. As former Vice Chief of Space Operations General Thompson noted, the U.S. is subjected to daily low-threshold attacks, including jamming, spoofing, radio frequency interference, and even laser dazzling of intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) assets. While these threats are discussed in congressional hearings, they rarely make mainstream news—most reporting is confined to the defense and aerospace trade press.

Another reason for the lack of public awareness is that many policymakers don’t view these attacks as damaging enough to be classified as acts of war. I’ve argued that they should be considered acts of war, especially when they target critical infrastructure. Rather than focusing on space as an environment to be protected, we should prioritize critical space infrastructure—the assets essential to our economy, national security, and daily life. GPS, satellite communications, and nuclear missile warning systems are prime examples of what must be defended. Not every commercial or civil space asset falls into this category, but those that do require serious protection and deterrence measures.

There are also competing ideological camps in the D.C. policy sphere: “space security” advocates versus traditional national security strategists. Many in the Space Force and government use the term “space security” assuming it conveys a military posture, but in reality, the term was created by arms control advocates like Plowshares and the Space Security Index. Their focus is not on protecting national interests but on preserving space as a peaceful, shared environment. This group aligns with efforts to limit debris creation and prevent space-based weapons, particularly kinetic ASATs.

On the other hand, national security advocates recognize that adversaries—China and Russia in particular—are already developing and deploying space weapons, holding U.S. assets at risk. Yet, instead of taking concrete action, U.S. policymakers have tried to appease both sides, resulting in rhetoric about responsible behavior with no real deterrence capability to back it up.

Ironically, the biggest contributors to space debris are not U.S. weapons tests but China and Russia’s non-passivationpractices—failing to drain propellant and batteries from spent upper stages, leading to uncontrolled explosions. Even European studies confirm this, yet U.S. policy remains fixated on restricting our own ASAT capabilities while China and Russia continue testing unchecked.

Even during the Obama administration, when official policy opposed space weaponization, China was actively conducting ASAT tests, deploying systems, and destroying satellites. Eventually, U.S. officials had to acknowledge space as a warfighting domain—though the first person to say this publicly was reprimanded. Now, under the Biden administration, there’s been a renewed shift toward strategic denial—hoping that if the public doesn’t think about these threats, policymakers won’t have to address them. But this approach hasn’t worked; the situation has only deteriorated.

With programs like Iron Dome America

and increasing awareness of space-based threats, I hope the current administration and new Congress take these issues more seriously than we’ve seen over the past two or three presidential terms.

About Christopher Stone

Christopher Stone is a prominent figure in space policy, currently serving as a Senior Fellow for Space Deterrence at the National Institute for Deterrence Studies, where he focuses on research related to space warfare strategies and deterrence, particularly in the context of great power competition; he previously held a position as a Special Assistant to the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Space Policy at the Pentagon, giving him significant experience in the field of U.S. space policy development at a high level.

For more information, reach out to Chris at cstone@thinkdeterrence.com