"The Future of Space Is Reusable, Fast, And Built To Last” From Air Force Mechanic to BlackStar Orbital Founder, Christopher Janette's Mission to Revolutionize What a Satellite Can Be (Part 1)

Discover how Air Force veteran Christopher Janette is revolutionizing satellite technology with BlackStar Orbital's hypersonic, reusable spacecraft that can return from orbit and land on conventional runways, positioning the US to address critical space security challenges.

Under the scorching California sun at Travis Air Force Base, a 21-year-old Air Force maintainer performs a task that would terrify most civilians: pushing million-dollar jet engines to 110% capacity during critical test runs. It's the kind of responsibility that requires absolute precision—one miscalculation could be catastrophic. Yet for Christopher Janette, these high-stakes tests were just the beginning of a classified journey that would eventually intersect with America's most sensitive national security concerns in orbit.

As Chinese hypersonic weapons and counter-space capabilities advance at an alarming rate—developments that Pentagon officials privately describe as "game-changing"—traditional American satellites have become vulnerable in ways unimaginable during the Cold War. This is the story of how a young airman who once wrote "I am going to be an engineer" in his childhood journal emerged from the shadows of military aerospace to pioneer "hypersonic satellites" that could shift the balance of power in the new orbital battlefield.

In Part 1, we explore Janette's journey from Air Force mechanic to space entrepreneur, the current competition between the US, China, and Russia in space, and BlackStar Orbital's revolutionary approach to creating reusable satellites that can return from orbit to land on conventional runways.

You've had an impressive journey from the Air Force to founding space companies. What initially sparked your passion for space, and was there a specific moment that made you decide to dedicate your career to space development?

"Like many from my generation, I was shaped by the sci-fi movies of the '80s—Back to the Future, E.T., Close Encounters, Star Wars, and Star Trek. Star Wars captured the thrill of space adventure, while Star Trek showed how space ties into humanity’s future. They were more than entertainment—they planted seeds.

But the real turning point came on September 9, 1995. My parents had given me an Estes rocket kit, and I launched it in a nearby construction lot in Ashburn, Virginia. That day, I wrote in my journal: 'I am going to be an engineer.' I remember the sky, the excitement, and that sense of clarity.

That passion led me to the Air Force, where I became an avionics maintainer. It was foundational. Working on jets taught us systems engineering from the ground up—hands-on with flight computers, control systems, and engines. I was stationed at Travis AFB, and by 21, I was in the cockpit for test runs, pushing engines to 110%. That kind of responsibility gave me real confidence in complex systems.

Later, while stationed in Japan during the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, I saw firsthand how wide the gap was between what tech could do and what was actually being used. That moment reinforced my belief that we needed to innovate faster—and smarter.

Throughout my career, I told colleagues I wanted to get into the space industry. Not just join it, but help build it. I wanted to work alongside the pioneers I’d been reading about for years. Some of them are now mentors or peers, and we’ve ended up 'vibe matching'—sharing the same mission and momentum.

Family also played a big role. One of my parents worked with ABC News covering early shuttle launches and later joined Orbital Sciences. I once watched a Pegasus launch seated next to an astronaut. Space wasn’t some distant, abstract thing—it was part of our world. That grounding, plus parents who encouraged whatever their kids loved, made a huge difference.

If we want a culture of achievement, it starts with making big goals feel reachable at home."

In your experience working with both NASA and private companies like SpaceX, how do you assess the current state of competition between the US, China, and Russia in space technology and exploration? Where do you see our vulnerabilities and strengths?

"The US continues to lead in areas like private sector innovation and launch capability—SpaceX being a prime example. Our commercial partnerships, bolstered by programs like SBIR, give us an edge in agility and technology like AI and reusable vehicles. But China is closing the gap rapidly. Their centralized model allows them to industrialize and scale faster than we can, especially in hypersonics, space station development, orbital logistics, and lunar operations. They're already issuing RFQs for Mars sample returns. They’re not just watching—they’re in the race, eyes on the same prize.

Where we struggle is procurement speed and bureaucracy. The time between contract award and first payment can take months, which slows innovation. China and our other adversaries treat this as both a sprint and a marathon—and they act accordingly. That mindset difference is critical.

Russia presents a different kind of threat. They’ve fallen behind in innovation but remain dangerous in specific strategic areas—space-based countermeasures, and now, orbital nuclear deterrence. Their playbook is different, but it’s still effective.

The US also faces serious vulnerabilities in space domain awareness and the resiliency of our orbital infrastructure. We still think of space as a passive environment—deploy, observe, communicate—but that model no longer works. We need systems that can actively maneuver, repair, and defend themselves. That’s why the Space Force’s upcoming “space statement and maneuver” challenge is so important. It’s also where platforms like BlackStar can make a real difference.

I was part of a workshop last year envisioning what a 2027 satellite might look like. We’re heading toward modular, AI-enabled platforms—BlackStar, True Anomaly, K2 Space—capable of evolving with mission needs. There’s also exciting work happening at Proteus Space, developing tools for rapid satellite prototyping. That’s the future—fast, adaptable, intelligent systems.

Of course, we want space to remain a domain of peace—and it should. But like the Cold War, we’re also in a state of quasi-war. There were no orbital incidents back then, but that was luck and deterrence. We can’t afford to rely on luck this time around.

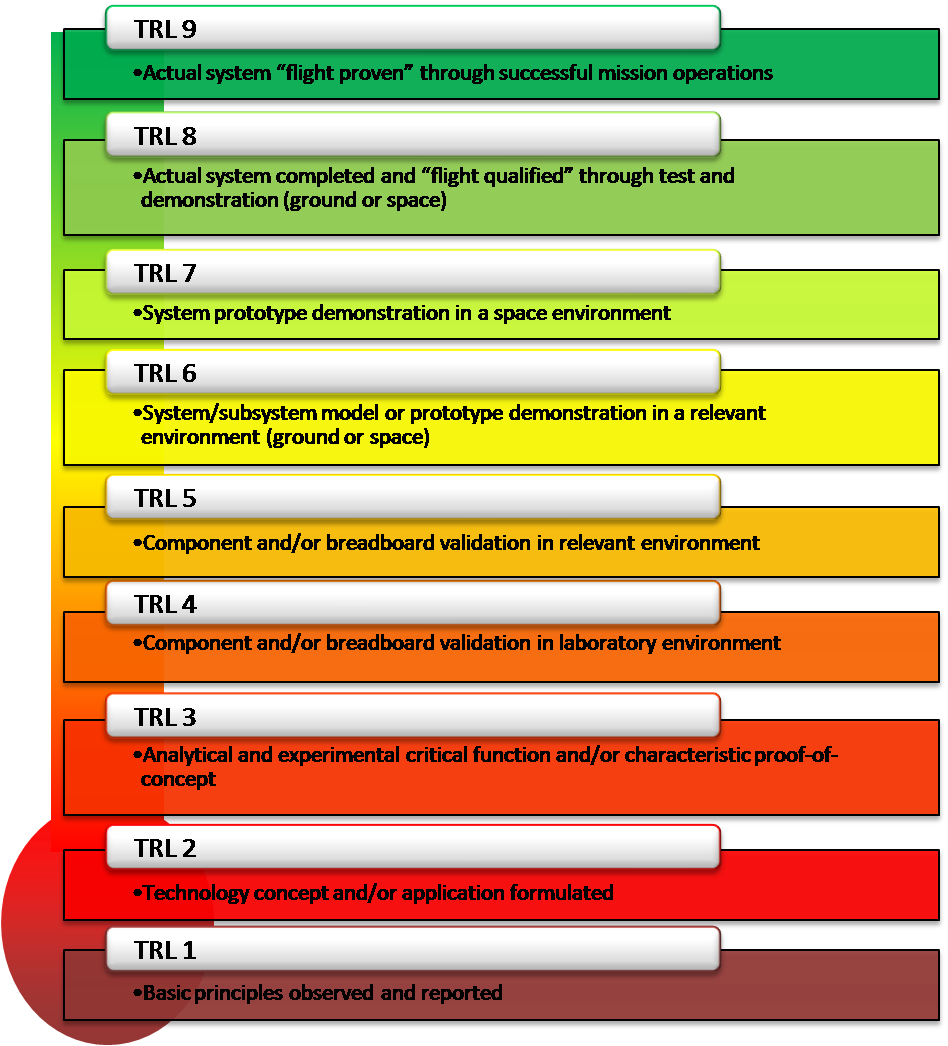

There’s also precedent for the level of tech we may need. People forget that Reagan’s Star Wars program wasn’t just theoretical. We had working beam and particle weapon systems—TRL-9 tech. In 1989, the BEAR program launched a rocket that accelerated hydrogen atoms to six-tenths the speed of light. We effectively had a miniature Death Star. Do we want to go back there? Probably not—but with today’s threats, we might have to.

When comparing China and Russia, China is clearly the long-term competitor. They have the scale, the ambition, and a maturing technology base. I don’t think we’re heading into a world with one hyperpower, but rather a group of superpowers competing for global market share—similar to the Cold War, but economically driven.

Low Earth orbit is going to become congested and contested. By 2040–2045, I expect to see a Chinese private space station, not just their national platform. The US needs to respond in kind—not just to match capability, but to lead in zero-G research and commercial activity. That’s where the real long-term value lies.

Beyond the major players, we’re seeing strong moves from Europe and India. India is advancing rapidly and is likely to have a manned lunar presence—and maybe even its own station—by 2045. Their engineering culture runs deep, and they bring a cosmological perspective to space that makes them natural partners, not rivals.

Europe, meanwhile, is stepping out of America’s shadow. With increasing defense budgets, we’re seeing European investment in next-gen launch and reusable systems. Startups like Polaris and Space Rider are developing vehicles that rival what we're doing here. Space Rider, for example, is building a hypersonic capsule—different from BlackStar, but solving similar problems. They use parachutes instead of wings, but their goal is the same: reusable, versatile space infrastructure.

Europe doesn’t want to be the junior partner anymore. They have the population, the education base, and the motivation to compete. It’s all about market share now. And regionally, you’ve got China, Russia, and India operating in close proximity—with their own historic rivalries and overlapping ambitions. I wouldn’t be surprised to see those three engaged in their own space race, especially around lunar and resource exploration.

That complexity gives the US an opportunity to triangulate. Strategically, we’re positioned to align with certain players, offset others, and remain the key driver of global space norms. But only if we keep moving. As I’ve said before, when you’re on top, every direction is down—so the only real choice is to keep climbing."

Your mention "revolutionizing what satellites can do by reinventing what a satellite is" at BlackStar Orbital. Could you elaborate on this vision and how it differentiates from conventional approaches in the industry?

“If this were a videotaped interview, I'd be smiling right now," Janette begins enthusiastically, "because at BlackStar Orbital, we're absolutely reinventing what satellites can do by redefining what a satellite is. We're developing hypersonic satellites that launch and operate like traditional payloads—but return home like spaceplanes. The future is reusable, fast, and built to last. Our goal is to overcome the limitations and challenges inherent in the disposable space economy."

He describes their current prototype: "Our MVP is two meters long and looks like a miniature spaceplane. We have shuttle heritage—in fact, one of our key advisors is a former shuttle pilot and International Space Station Commander."

Janette traces the origin story of BlackStar: "This actually goes back to when I was living just 15 minutes from Kennedy Space Center, before my time at SpaceX and NASA KSC. I was working on a foreign ocean launch project, exploring non-traditional methods for a more cost-effective launch system. That's when we came across research from the 1960s by Bob Truex, involving a ballast-stabilized vehicle that could be deployed into the ocean. You'd fill up the ballast tank, the rocket would orient vertically, and then launch."

This exploration led to a pivotal conversation: "We brought the idea to someone who would later become our advisor—retired Colonel Terry Birds, a former shuttle pilot and ISS commander—and asked, 'What do you think about the sea ring?' He replied, 'Have you looked into hypersonics?' And we said, 'What about a pre-positioned hypersonic asset on orbit?' That's how BlackStar began—as a quintessential dual-use technology."

Janette's career path supported this development: "After several years working in stealth, I moved to the center, working on programs like Starship and serving as lead engineer for NASA's KPLS-S2 program. I was console operator for numerous propellant loads—everything from Crew Dragon to Starliner to Artemis, and of course, national security launches. We handled dozens—nearly every cryogenic launch from the center passed through my team's hands on the Cape side."

After completing that work, he refocused on BlackStar: "I spent several months working on the side to redevelop and reinvigorate the concept. We secured funding in late 2019 and early 2020 to explore the program. Then COVID hit, which gave us the opportunity to really dive into the books and evaluate what would define the mid-21st century and beyond. All signs pointed to BlackStar."

Blackstar Orbital lands spacecraft facility at Sierra Vista Municipal Airport

He explains the core concept in simple terms: "It's an elegant and straightforward system. You essentially have a hypersonic lifting body that encapsulates a small-sat payload. Instead of using traditional, disposable BoxSats, we're mounting the payload on a lifting body, launching it via a standard ESPA Grande-class vehicle—and then bringing it back to Earth. We can land at any of the 14,000 runways worldwide that are over 5,000 feet long."

The company is making significant progress: "It's an incredibly exciting time to be doing this. We've secured investors, and we're now about to begin Phase Two—valued at $1.9 million—down in Arizona. It's off to the races. The future is here, and it's reusable."

With your extensive experience in hypersonic technology and space systems, how would you assess the current gap between U.S. capabilities and China's rapid advances in fractional orbital bombardment systems and hypersonic glide vehicles?

"The US is behind in operationalizing hypersonic glide vehicles," Janette states directly. "China has demonstrated advanced maneuverability and re-entry capabilities, which enables them to execute unpredictable attack trajectories like those I mentioned earlier."

This represents a fundamental shift in strategic balance: "We're seeing a massive shift from Cold War deterrence that was based on predictable ballistic missile paths. During the Reagan 'Star Wars' era, systems were designed so a Nike Sprint missile could intercept a Russian ICBM following a plottable trajectory."

He identifies the core challenges for the US: "While the US is now making progress, our biggest challenge lies in bridging the gap between research and operational deployment. The private sector is playing a crucial role in helping us catch up. However, procurement delays, risk aversion, and insufficient testing infrastructure will continue to slow us down until we fundamentally rethink our approach to bringing these systems to market."

Janette advocates for a more aggressive development approach: "We need to return to the development pace we had in the 1950s. Consider the sixth-generation fighter program in the US Air Force—they're planning deployment for the late 2030s or 2040s. In the 1950s, if Uncle Sam needed a new fighter, you'd see a prototype in flight tests just 24 months after the initial request. We can't afford to wait for the next Kelly Johnson to emerge. We need to embody that innovative spirit ourselves."

To address the gap, he prescribes specific measures: "Closing this gap requires more frequent hypersonic flight testing and a focused investment in counter-hypersonic defense capabilities. Operational space planes like BlackStar can provide the rapid response capabilities we need. This is precisely where our system excels—offering an alternative to expendable vehicles and enabling routine access to low Earth orbit and hypersonic flight regimes for intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance, testing, and deterrence."

He concludes with a realistic assessment of what's needed: "We're committed to making this happen. The question isn't if but when, and success will likely come from a confluence of funding sources—both private venture capital and public investment working in tandem."

Space has traditionally been viewed as a sanctuary domain, but we're seeing increased militarization. Drawing from your experience across multiple aerospace companies, what are the most misunderstood aspects of space as a military domain that the public doesn't grasp?

Janette offers a concise observation before diving deeper: "It takes just one large solar flare to knock us back to 1900."

Then he addresses the core misconception: "The biggest misconception is that space remains a sanctuary. The idea that it's still an uncontested or neutral environment simply hasn't held true—and hasn't been accurate for decades. Space is now a fully operational domain for national security, just like land, air, and sea."

He explains the current reality of space warfare: "What most people don't realize is that satellites are already engaged in non-kinetic warfare. Jamming, spoofing, and cyber attacks facilitated by rendezvous proximity operations are happening in real time. Nations are actively testing their direct-ascent anti-satellite weapons, known as ASATs. If you're wondering what an ASAT is, a Google search will show you images from the 1980s of an F-15 launching a missile straight up—and that's essentially what they are."

The militarization of space is more advanced than many realize: "Countries are deploying dual-use systems that can function as both kinetic and electronic warfare assets while positioning preemptive orbital threats. I'd even go a step further—any satellite equipped with a camera for Earth observation is just one phone call away from becoming an ISR (Intelligence, Surveillance, Reconnaissance) asset."

This leads to his conclusion about the strategic reality: "We need to start thinking about space security beyond just avoiding debris or preventing conflicts. The reality is, whoever controls space controls the economic and military high ground. That means autonomous maneuvering, active defense capabilities, and rapid-response systems are no longer optional—they're essential."

Conclusion

As Christopher Janette and his team at BlackStar Orbital work to redefine what satellites can be, they stand at the intersection of commercial innovation and national security. The hypersonic satellite concept they're pioneering could transform how we think about space assets—from disposable, vulnerable systems to adaptable platforms that can be modified, updated, and retrieved as needed.

"Space is becoming a contested domain," Janette emphasizes. "The future isn't just about getting to orbit—it's about returning safely, adapting quickly, and building systems that can evolve with emerging threats."

In Part 2 of our conversation, we'll explore BlackStar's strategic advantages in an increasingly competitive global landscape, examining how their technology addresses emerging threats from China's sea-based launch capabilities and offers new solutions for commercial space operations. We'll also dive deeper into the company's vision beyond Earth orbit and how their modular, reusable approach might reshape the economics of space exploration for decades to come.

About Christopher Jannette

Christopher "CJ" Jannette leads BlackStar Orbital as President/CEO, developing modular satellite platforms. His aerospace career includes work on Falcon Heavy, Artemis 1, and SpaceX Dragon missions. A decorated veteran, CJ now focuses on hypersonic vehicle development and autonomous space operations while consulting for VC firms and United Paradyne Corporation. BlackStar aims to revolutionize spaceflight with hypersonic satellites that return from orbit.

For more information, contact Christopher at ceo@spacedrone.io

Additional Resources:

BlackStar Orbital Announces Spacecraft Manufacturing And Test Facility In Sierra Vista

Titusville-based Blackstar Orbital Collaborates on New Spaceport in Ecuador | TalkOfTitusville.com